|

|

- Search

| Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab > Volume 27(1); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on body mass index (BMI) of children and adolescents.

Methods

From May to July 2020, the obesity rate of children and adolescents was compared retrospectively to the corresponding rate in the same period in 2019. The change in height, weight, and BMI of the girls who received a gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) for precocious puberty (n=53) and the controls (n=31) who visited a growth clinic for early breast budding but were not treated with GnRHa in the first half of 2020 were compared to the corresponding change in the first half of 2019 using a paired t-test.

Results

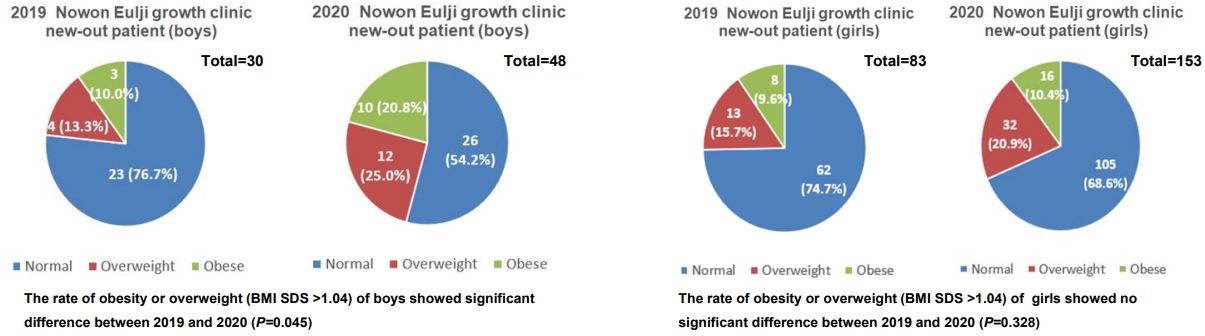

The rate of overweight or obesity in new outpatients (n=113, 83 girls, 30 boys) who visited growth clinics from May to July 2019 was 25.3% for girls and 23.3% for boys. The corresponding rate for the same period in 2020 (n=201, 153 girls, 48 boys) was 31.4% for girls and 45.8% for boys. There was a significant increase in the rate of overweight or obesity. The BMI of the GnRHa treatment group increased significantly from May to July 2019 than during the same period in 2020 (P<0.01). There was no significant difference in BMI between those periods in the control group.

During the social distancing period, the incidence of obesity was higher in boys than in girls. The obesity rate in girls who visited the growth clinic for early breast budding during routine follow-ups did not increase.

The novel coronavirus disease outbreak occurred in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei province, China [1,2]. It was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [3]. This disease started as a local epidemic that eventually reached pandemic proportions, as declared by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020 [4]. On January 20, 2020, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was registered in Korea [2]. That day, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) raised the alert level from 'blue' (level 1) to 'yellow' (level 2) out of the country's 4-level national crisis management system [5]. On January 27, 2020, the KCDC raised the alert level to 'orange' (level 3). As the number of COVID-19 cases continued to increase in the country, the KCDC raised the alert level to 'red' (level 4) on February 23, 2020, prompting the Ministry of Education to postpone the beginning of the new school year [6].

As part of the response strategy to the COVID-19 pandemic, the population was advised to embrace social distancing, a powerful means of reducing the transmission of infectious diseases. However, maintaining social distance for an extended period reduces its effectiveness, and the socioeconomic impact is enormous [7]. More than 5 million students and their families stayed at home because all schools were closed until May 2020 [8].

Due to COVID-19, the term "quarantine-15" has become popular and refers to the weight gain associated with the rapid reduction in physical activities and increased food consumption. Many social problems have also emerged due to this degradation of body appearance [9]. After May 2020, we noticed a new trend of weight gain among most children who visited our growth clinic due to puberty evaluation or short stature. Parents and children complained of decreased activities because of school closure.

In this study, we aimed to determine whether childhood obesity has increased after school closure. We compared the obesity rate of new outpatient patients visiting the growth clinic before and after social distancing. In addition, we compared the body mass index (BMI) between the 2 groups: (1) girls who were diagnosed with precocious puberty and on gonadotropin releasing-hormone agonist (GnRHa) therapy and (2) girls who were regularly followed up in the growth clinic for breast budding without a GnRHa therapy, either because their bone age was lower than their chronological age or because they had a peak luteinizing hormone level below 5 mIU/mL after a GnRHa stimulation test.

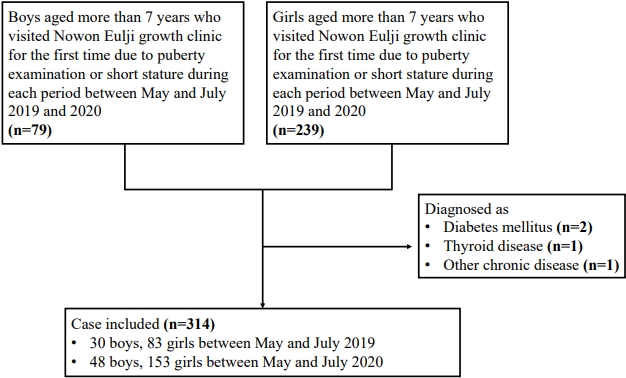

A total of 201 patients (48 boys, 153 girls) who visited the Nowon Eulji growth clinic for the first time requesting a puberty examination or for short stature between May and July 2020 (after the social distancing period following the COVID-19 outbreak) were included in the study. In addition, 113 patients (30 boys, 83 girls) who visited the clinic between May and July 2019 were included. Four patients who were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (n=2), thyroid disease (n=1), or another chronic disease (n=1) were excluded (Fig. 1). The participantsŌĆÖ BMIs before and after social distancing were compared. The participants were at least 7 years old.

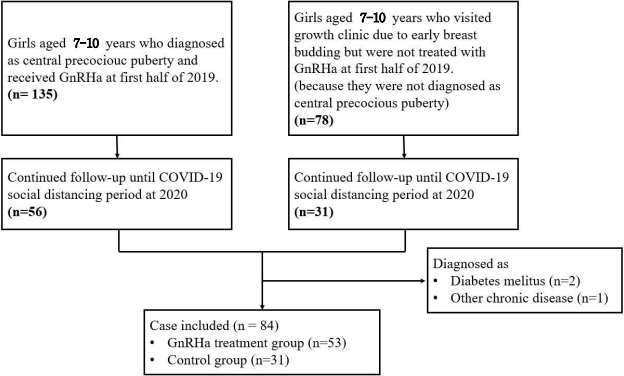

The girls were divided into 2 groups: the GnRHa treatment group, which included 53 girls who received GnRHa for precocious puberty, and the control group, which was made up of 31 girls who visited our growth clinic due to early breast budding but were not treated with a GnRHa because they were not diagnosed with central precocious puberty. Three patients who were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (n=2) or another chronic disease (n=1) were excluded (Fig. 2). We compared the weight, height, BMI, bone age, chronological age, and Tanner stage between 2019 and 2020 of each group.

In the GnRHa treatment group, 4 different measurements of the height, weight, and BMI of the girls were obtained: at the start and end of the first half of 2019 and 2020. In the control group, during the same period, 2 measurements of their height, weight, and BMI were obtained: at the end of the first half of 2019 and 2020.

We analyzed their height, weight, and bone age using a retrospective chart analysis.

Persons with a BMI above 85th percentile (=BMI standard deviation score [SDS] more than 1.04) according to the Korean children and adolescent growth chart (published by Korean CDC) were considered "overweight." [10].

We analyzed the differences in height, weight, BMI, and bone age of new outpatients between 2019 and 2020 using Student t-test. The difference in the overweight or obesity rate of new outpatients and difference in the Tanner stage between the GnRHa treatment group and control group were analyzed using the chi-square test, while the differences in height, weight, and BMI during the 5 months of each year in the GnRHa and control group were analyzed using a paired t-test. Factors affecting the BMI were analyzed using multiple linear regression. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 24.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

The patient group was stratified according to sex.

The difference between the chronological age and the bone age of boys tended to be higher in 2020, but it was not statistically significant (-0.2 vs. 0.0. P=0.481) (Table 1).

The rate of obesity or overweight (BMI SDS >1.04) of boys increased from 23.3% (7 patients) in 2019 to 45.8% (22 patients) in 2020; this difference was statistically significant (P=0.045). For girls, 25.3% (21 patients) and 31.4% (48 patients) of all new patients were obese or overweight in 2019 and 2020, respectively; this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.328) (Fig. 3).

The girls in the GnRHa treatment group and control group had the same race and nationality. There was no significant difference in age (P=0.057) and obesity rate (P=0.617) between the 2 groups.

The girls in the GnRHa group were injected with a GnRHa for an average of 22.7┬▒4.0 months. During the first 5 months of 2019, the average height (SDS) of the patients in the GnRHa group increased by 2.4┬▒0.7 cm from 135.0┬▒5.6 (0.8┬▒0.9) to 137.4┬▒5.5 (0.8┬▒0.8) cm. Their average weight (SDS) increased by 1.8┬▒1.4 kg from 33.7┬▒5.7 (0.8┬▒0.8) to 35.4┬▒6.0 (0.8┬▒0.8) kg. Their average BMI (SDS) increased from 18.4┬▒2.2 (0.6┬▒0.9) to 18.7┬▒2.2 (0.6┬▒0.9) kg/m2, but this difference was not statistically significant.

In contrast, for the first 5 months of 2020, the average height (SDS) of patients in the GnRHa group increased by 2.3┬▒0.8 cm from 140.7┬▒5.5 (0.7┬▒0.8) to 143.0┬▒5.6 (0.6┬▒0.8) cm. Their average weight (SDS) increased by 3.1┬▒2.0 kg from 39.2┬▒6.9 (0.9┬▒0.8) to 42.3┬▒7.8 (1.0┬▒0.9) kg. Their average BMI (SDS) increased by 0.9┬▒0.9 from 19.7┬▒2.6 (0.8┬▒0.9) to 20.6┬▒2.9 (1.0┬▒1.0) kg/m2. Their bone age increased from 10.9┬▒0.8 in 2019 to 11.4┬▒0.7 in 2020.

The proportion of obese or overweight patients increased from 28% (15 patients) in 2019 to 51% (27 patients) in 2020 (P=0.017) (Table 2).

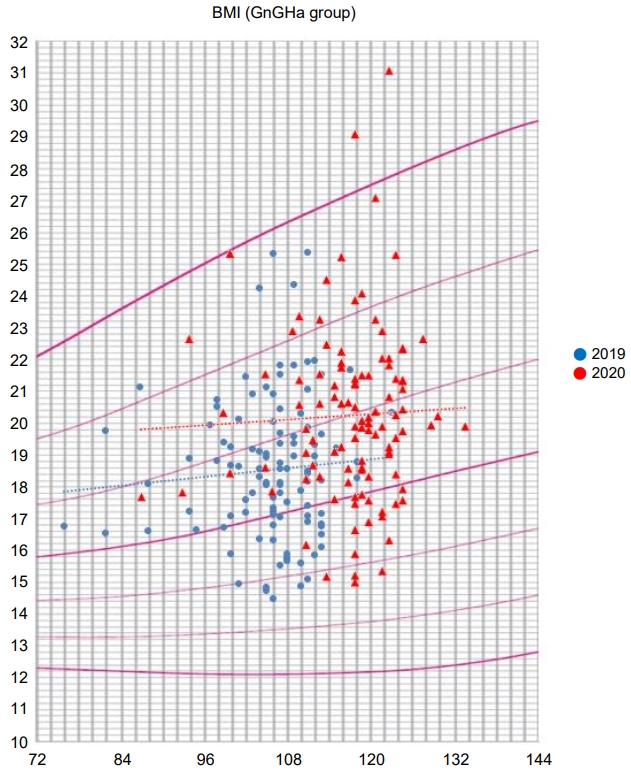

However, a scatter chart of the BMI distribution in 2019 and 2020 shows that the proportion of highly obese patients with more than 2 SDS increased in 2020 compared to 2019 (Fig. 4).

Between 2019 and 2020, the height (SDS), weight (SDS), and BMI (SDS) of the control group increased from 128.6┬▒5.5 (-0.39┬▒1.2) to 134.8┬▒5.7 (-0.31┬▒1.0) cm, 29.3┬▒5.3 (-0.05┬▒1.2) to 34.3┬▒6.6 (0.13┬▒1.1) kg, and 17.6┬▒2.6 (0.19┬▒1.2) to 18.8┬▒3.0 (0.39┬▒1.2) kg/m2. The difference in BMI was not statistically significant (Table 3).

In the GnRHa treatment group and the control group, the multiple linear regression analysis revealed that the factors affecting the last measured BMI SDS in 2020 were chronological age and bone age at the initial visit and last measured Tanner stage (r2=0.389, P=0.0.34) (Table 4).

In this study, we compared the percentage of obese patients among new outpatients who visited the growth clinic before and after social distancing due to COVID-19. There was no significant difference in the proportion of overweight or obese patients among the girls (23.3% vs. 31.4%, P=0.328). However, the proportion of overweight or obese patients among the boys increased significantly between the 2 periods (23.3% vs. 45.8%, P=0.045).

A possible reason for this sex difference in the obesity rate is that boys are likely to be more physically active than girls [11]; thus, the effect of reduced physical activity due to social distancing may be greater in boys than in girls. Therefore, we can assume that high normal weight or overweight boys were more likely to transition to obesity than girls. Additionally, the percentages of the chief complaint were different between boys and girls. We enrolled boys who visited the growth clinic due to short stature (n=18, 60%) or precocious puberty (n=12, 40%) and girls who visited due to short stature (n=21, 25%), or early breast budding (n=62, 75%). This means that our findings do not fully reflect the obesity level of all children and adolescents.

Although the difference between chronological age and bone age in boys who visited the clinic after social distancing was not statistically significant, there was a slight increase. This was probably due to the increased rate of obesity [12]. For both boys and girls, BMI (SDS) tended to increase in patients with a lower chronological age (r=-0.12 and P=0.03) and higher Tanner stage (r=0.18 and P=0.002).

In this study, girls who visited the growth clinic due to early breast budding were stratified into 2 groups according to their GnRHa treatment status. We compared the changes in height, weight, and bone age of these girls between 2019 and 2020. The BMI of girls who received GnRHa treatment increased from 18.7┬▒2.2 in 2019 to 20.6┬▒2.9 in 2020. In contrast, the BMI of the girls in the control group showed no significant difference between 2019 and 2020.

There is some evidence that over weight or obesity is associated with precocious puberty [13,14]. Previous studies on the effects of GnRHa on BMI have controversial findings. Some studies have reported a small or no difference in BMI [15,16], while other studies have shown a higher BMI after GnRHa therapy [17,18]. In this study, no significant change in BMI was observed in the first 6 months after GnRHa administration. However, after 6 months of GnRHa, a gradual increase in BMI was observed, and this trend was maintained during the social distancing period. Therefore, based on our findings, the impact of social distancing on childhood obesity is not clear. In addition, the absence of BMI differences in the control group (no GnRHa treatment) between 2019 and 2020 could be due to regular hospital visits for weight control.

Mask wearing due to COVID-19 contributed to a reduction in the number of patients who visited the pediatric clinic because of viral illness (21,509 patients in 2019 vs. 14,816 patients in 2020). However, the number of children visiting the growth clinic for short stature, precocious puberty, and obesity increased (7,022 patients in 2019 vs. 7,495 patients in 2020). Therefore, we can assume that a reduction in children's physical activity due to COVID-19 has a significant impact on their growth and obesity.

As of December 2020, several studies on the effect of decreased physical activity due to COVID-19 on endocrine metabolic diseases such as diabetes and thyroid diseases in adults have been conducted [19-21]. Similarly, studies on endocrine diseases in children and adolescents have also examined the effects of social distancing due to COVID-19, but the research is still limited compared to adults. Besides, more published studies focused on changes in incidences and glycemic control in children and adolescents during periods of social distancing [22,23]. In response to the limited number of studies, we evaluated the changes in the incidence of obesity in children and adolescents following the adoption of behavioral changes due to COVID-19. We noted concerns by parents of children visiting the growth clinic about their children's weight gain since the closure of the schools.

In prior studies, the subjects were children and adolescents who visited hospitals for treatment, which indirectly suggests that obesity could increase even in normal children and adolescents although the findings were not generalizable.

However, in this study, we targeted children who visited a pediatric growth clinic. Therefore, we could compare the anthropometric changes of relatively healthy children with those from previous studies because the purpose of hospital visits was to check the changes in height and weight and puberty.

Therefore, our results could be more representative of healthy children and their obesity rates. Furthermore, consistent with previous studies, approximately 70% of our study subjects were normoweight, and about 30% were overweight or obese [17,24].

However, our study has several limitations. First, there were relatively few male outpatients and controls. Second, although the study subjects were healthy children who visited the hospital intentionally, the increase in obesity was possibly lower than the actual change because of selection bias in the social distancing effects analysis. Third, only BMI was measured using a retrospective chart analysis; therefore, we could not monitor the changes in other metabolic syndrome parameters. Fourth, we could not obtain the BMIs before 2019. Finally we enrolled patients who visited a single center.

Therefore, a large-scale study involving the national population is needed. However, the annual examination of students was not conducted this year due to COVID-19, and this could limit future research. Recent reports of successful vaccine development indicate p ossible elimination of COVID-19, but the population should prepare for "post-pandemic" childhood and adolescent health problems. In this regard, an urgent national study on the changes in the incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome due to decreased physical activity among children and adolescents is warranted.

In conclusion, the percentage of overweight or obese children who visited the growth clinic during the social distancing period compared to the same period in the previous year increased significantly in boys. Girls who received GnRHa had higher BMI and bone age during the social distancing period compared to the same period in the previous year, and the BMI did not differ in the control group (no GnRHa treatment) during the same period. Therefore, obesity in boys with relatively much decreased activity should be controlled. Importantly, routine follow-ups through regular hospital visits are recommended for successful control of obesity. Furthermore, national health examinations to evaluate obesity of children are necessary during the social distancing period.

Notes

Ethical statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Eulji University (approval No. EMCS 2020-12-014). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms. Hye-young Han, Nowon Eulji Hospital, for her technical assistance in this study.

Fig.┬Ā2.

Flow chart of the cases who enrolled in the gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist treatment group and the control group. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Obesity rate of new outpatients in 2019 and 2020. BMI, body mass index; SDS, standard deviation score.

Fig.┬Ā4.

Body mass index (BMI) distribution of patients in the gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) treatment group in 2019 and 2020.

Table┬Ā1.

Differences in chronological age, bone age, Tanner stage, height, weight, and BMI of new outpatients between 2019 and 2020

Table┬Ā2.

Differences in chronological age, bone age, height, weight, and BMI of the GnRHa treatment group between 2019 and 2020

| Variable |

2019 (n=53) |

2020 (n=53) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Later | P-value | Initial | Later | P-value | |

| CA (yr) | 8.6┬▒0.6 | 9.0┬▒0.6 | <0.01 | 9.6┬▒0.6 | 10.0┬▒0.6 | <0.01 |

| Height (cm) | 135.0┬▒5.6 | 137.4┬▒5.5 | <0.01 | 140.7┬▒5.5 | 143.0┬▒5.6 | <0.01 |

| Height (SD) | 0.8┬▒0.9 | 0.8┬▒0.8 | <0.01 | 0.7┬▒0.8 | 0.6┬▒0.8 | <0.01 |

| Weight (kg) | 33.7┬▒5.7 | 35.4┬▒6.0 | <0.01 | 39.2┬▒6.9 | 42.3┬▒7.8 | <0.01 |

| Weight (SDS) | 0.8┬▒0.8 | 0.8┬▒0.8 | 0.39 | 0.9┬▒0.8 | 1.0┬▒0.9 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.4┬▒2.2 | 18.7┬▒2.2 | <0.01 | 19.7┬▒2.6 | 20.6┬▒2.9 | <0.01 |

| BMI (SDS) | 0.6┬▒0.9 | 0.6┬▒0.9 | 0.98 | 0.8┬▒0.9 | 1.0┬▒1.0 | <0.01 |

| ΔHeight (cm) | 2.4±0.7 | 2.3±0.8 | 0.63 | |||

| ΔHeight (SDS) | -0.1±0.1 | -0.1±0.1 | 0.60 | |||

| ΔWeight (kg) | 1.8±1.4 | 3.1±2.0 | <0.01 | |||

| ΔWeight (SDS) | 0±0.2 | 0.1±0.2 | <0.01 | |||

| ΔBMI (kg/m2) | 0.30±0.7 | 0.9±0.9 | <0.01 | |||

| ΔBMI (SDS) | 0±0.3 | 0.2±0.3 | <0.01 | |||

| Obesity or overweight rate, n (%) | 0.017 | |||||

| ŌĆāNormal | 38 (72) | 26 (49) | ||||

| ŌĆāObese or overweight | 15 (28) | 27 (51) | ||||

| ŌĆāŌĆāOverweight | 12 (22) | 20 (38) | ||||

| ŌĆāŌĆāObese | 3 (6) | 7 (13) | ||||

| Tanner stage | <0.01 | |||||

| ŌĆāStage 1 | 0 | 8 | ||||

| ŌĆāStage 2 | 29 | 12 | ||||

| ŌĆāStage 3 | 24 | 33 | ||||

| ŌĆāStage 4 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| ŌĆāStage 5 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| BA (yr)* | 10.9┬▒0.8 | 11.4┬▒0.7 | <0.01 | |||

| Peak LHŌĆĀ | 13.7┬▒13.4 | - | ||||

Table┬Ā3.

Differences in chronological age, bone age, height, weight, BMI, bone age, and obesity rate of the control group between 2019 and 2020

| Variable | 2019 (n=31) | 2020 (n=31) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA (yr) | 8.7┬▒0.9 | 9.7┬▒0.9 | <0.01 |

| Height (cm) | 128.6┬▒5.5 | 134.8┬▒5.7 | <0.01 |

| Height (SDS) | -0.4┬▒1.2 | -0.31┬▒1.0 | 0.28 |

| Weight (kg) | 29.3┬▒5.3 | 34.3┬▒6.6 | <0.01 |

| Weight (SDS) | -0.1┬▒1.2 | 0.13┬▒1.1 | 0.03 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.6┬▒2.6 | 18.8┬▒3.0 | <0.01 |

| BMI (SDS) | 0.2┬▒1.2 | 0.4┬▒1.2 | 0.08 |

| Obesity or overweight rate | 0.562 | ||

| ŌĆāNormal | 24 (77) | 22 (71) | |

| ŌĆāObese or overweight | 7 (23) | 9 (29) | |

| ŌĆāŌĆāOverweight | 3 (10) | 5 (16) | |

| ŌĆāŌĆāObese | 4 (13) | 4 (13) | |

| Tanner stage | <0.01 | ||

| ŌĆāStage 1 | 16 | 4 | |

| ŌĆāStage 2 | 12 | 11 | |

| ŌĆāStage 3 | 3 | 13 | |

| ŌĆāStage 4 | 0 | 3 | |

| ŌĆāStage 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| BA (yr)ŌĆĀ | 8.9┬▒1.3 | 10.3┬▒1.3 | <0.01 |

Table┬Ā4.

Correlation between body mass index and Tanner stage (TS) or initial chronological age and bone age

References

1. Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020;395:470ŌĆō3.

2. Kim JY, Choe PG, Oh Y, Oh KJ, Kim J, Park SJ, et al. The first case of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia imported into Korea from Wuhan, China: implication for infection prevention and control measures. J Korean Med Sci 2020;35:e61.

3. World Health Organization. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland), World Health Organization. 2020;[cited 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it.

4. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland), World Health Organization. 2020;[cited 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

5. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The updates of COVID-19 in republic of korea as of 5 April 2020 [Internet]. Cheongju (Korea), Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2020 Apr 5]. Available from: https://is.cdc.go.kr/upload_comm/syview/doc.html?fn=159220034100800.pdf&rs=/upload_comm/docu/0030/.

6. Ministry of Education South Korea. Deciding to postpone the opening of all elementary, middle and high schools nationwide and preparing supplementary measures for the protection and management of students entering China (COVID-19) [Internet]. Sejong (Korea), Ministry of Education, South Korea. 2020;[cited 2020 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/view.do?boardID=294&boardSeq=79829&lev=0&searchType=null&statusYN=W&page=9&s=moe&m=020402&opType=N.

8. Chosun Ilbo. Corona Blue... "Already for a month, I've been feeling stuffy and nervous." [Internet]. Seoul (Korea), Chosun Ilbo. 2020;[cited 2020 Mar 9]. Available from: https://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2020/03/09/2020030900148.htmla.

9. Yenhap News. Cheongju City's 'quarantine 15ŌĆÖ remarks to subordinate employees and demands disciplinary action against Grade 6 employees [Internet]. Seoul (Korea), Yenhap News. 2020;[cited 2020 August 28]. Available from: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20200723062000064.

10. Kim JH, Yun S, Hwang SS, Shim JO, Chae HW, Lee YJ, et al. The 2017 Korean National Growth Charts for children and adolescents: development, improvement, and prospects. Korean J Pediatr 2018;61:135ŌĆō49.

11. Telford RM, Telford RD, Olive LS, Cochrane T, Davey R. Why are girls less physically active than boys? Findings from the LOOK Longitudinal Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150041.

12. de Groot CJ, van den Berg A, Ballieux BEPB, Kroon HM, Rings EHHM, Wit JM, et al. Determinants of advanced bone age in childhood obesity. Horm Res Paediatr 2017;87:254ŌĆō63.

13. Ahmed ML, Ong KK, Dunger DB. Childhood obesity and the timing of puberty. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2009;20:237ŌĆō42.

14. Papadimitriou A, Nicolaidou P, Fretzayas A, Chrousos GP. Clinical review: constitutional advancement of growth, a.k.a. early growth acceleration, predicts early puberty and childhood obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:4535ŌĆō41.

15. Yoon JW, Park HA, Lee J, Kim JH. The influence of gonadotropin - releasing hormone agonists on anthropometric change in girls with central precocious puberty. Korean J Pediatr 2017;60:395ŌĆō402.

16. Arrigo T, De Luca F, Antoniazzi F, Galluzzi F, Segni M, Rosano M, et al. Reduction of baseline body mass index under gonadotropin-suppressive therapy in girls with idiopathic precocious puberty. Eur J Endocrinol 2004;150:533ŌĆō7.

17. Park J, Kim JH. Change in body mass index and insulin resistance after 1-year treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in girls with central precocious puberty. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2017;22:27ŌĆō35.

18. Kim SW, Kim YB, Lee JE, Kim NR, Lee WK, Ku JK, et al. The influence of gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist treatment on the body weight and body mass index in girls with idiopathic precocious puberty and early puberty. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2017;22:95ŌĆō101.

19. Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Sala C. COVID-19 and diabetes: Is there enough evidence? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22:943ŌĆō8.

20. Zhu L, She ZG, Cheng X, Qin JJ, Zhang XJ, Cai J, et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab 2020;31:1068. ŌĆō77. e3.

21. Khoo B, Tan T, Clarke SA, Mills EG, Patel B, Modi M, et al. Thyroid function before, during, and after COVID-19. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106:e803ŌĆō11.

22. Ceconi V, Barbi E, Tornese G. Glycemic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 lockdown: what comes after a "quarantine"? J Diabetes 2020;12:946ŌĆō8.

23. Tittel SR, Rosenbauer J, Kamrath C, Ziegler J, Reschke F, Hammersen J, et al. Did the COVID-19 Lockdown affect the incidence of pediatric type 1 diabetes in Germany? Diabetes Care 2020;43:e172ŌĆō3.

24. Park J, Hwang TH, Kim YD, Han HS. Longitudinal follow-up to near final height of auxological changes in girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog and grouped by pretreatment body mass index level. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2018;23:14ŌĆō20.