|

|

- Search

| Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab > Volume 28(Suppl 1); 2023 > Article |

|

┬Ę Type A insulin resistance syndrome presents variably among patients despite the same mutation in the INSR gene. For early detection and adequate treatment approaches, clinicians should consider genetic testing either in patients who lack both the characteristics of type 1 (islet auto-antibodies, low C-peptide levels) and type 2 (obese, dyslipidemia, fatty liver) diabetes or in nonobese patients with insulin resistance and ovarian hyperandrogenism.

To the editor,

Type A insulin resistance syndrome (IRS) is a rare congenital disorder caused by insulin receptor dysfunction arising from heterozygous mutations in the insulin receptor (INSR) gene. It is characterized by the triad of insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans (AN), and ovarian hyperandrogenism. The disorder is most commonly discovered around puberty due to the symptoms arising from ovarian dysfunction, which drives the synergistic effect of gonadotropin and insulin action on the ovaries [1,2]. At presentation, hyperglycemia is often not observed. When the ╬▓-cell compensatory response to insulin resistance is insufficient to regulate glucose metabolism, impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus develop, but patients rarely present with hypoglycemia [1,2].

We present the case of a 14-year-old girl with diabetes. Glucosuria was detected by a school urinary screening test 2 months prior. At presentation, she was not obese, with a height of 153.0 cm (standard deviation score [SDS], -1.02), weight of 46.5 kg (SDS, -0.6), and body mass index (BMI) of 19.9 kg/m2 (SDS, -0.2). She did not have a dysmorphic face, except for dental abnormalities, including crowding of the upper and lower teeth. She had no facial acne or AN. Coarse hair was observed on the patient's upper lip, chin, midline of the lower abdominal wall, and arms. We calculated a modified Ferriman-Gallwey score of 7 points (hirsutism is defined by a value Ōēź8 points). She was born at a gestational age of 40 weeks with a birth weight of 3,100 g. According to her mother, she had had darkened skin and hypertrichosis on her extremities since birth. At the age of 8 years, spontaneous thelarche occurred. She had received gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist treatment for central precocious puberty for 2.5 years at our hospital. At the age of 13 years, she experienced menarche, which was 1 year after the GnRH agonist treatment had ended. Her menstrual cycle was regular.

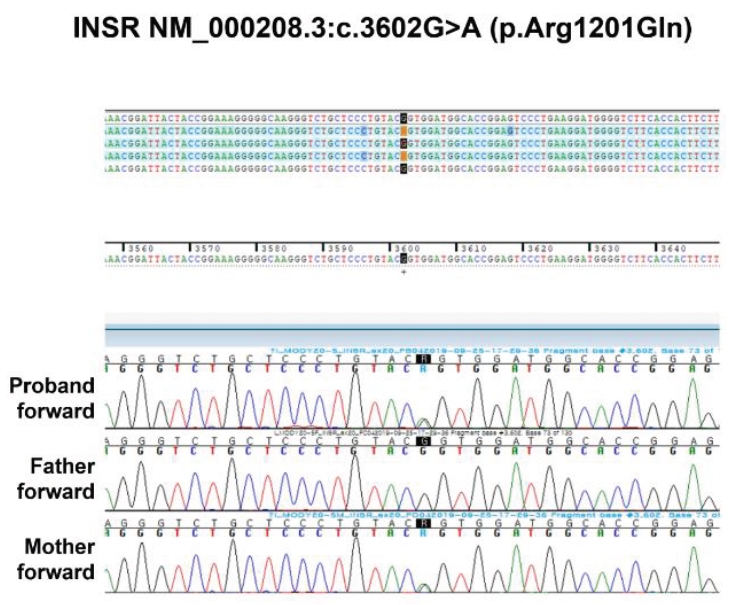

At presentation, her laboratory results were as follows: fasting plasma glucose, 179 mg/dL; C-peptide level, 1.8 ng/mL; insulin level, 34.8 lU/mL; homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance score, 15.4 points (cutoff value, Ōēź3.6 points); and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), 10.6% (Table 1). The results for islet cell auto-antibodies, insulin auto-antibodies, and glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies were negative. Her serum liver function; lipid profile results; and levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, estradiol, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate, sex hormone-binding globulin, and testosterone were within normal ranges. A next-generation sequencingŌĆōbased targeted gene panel for known maturity-onset diabetes of the young revealed a heterozygous mutation in the INSR gene, c.3602G>A (p.Arg1201Gln) (Fig. 1). This has been previously reported as p.Arg1174Gln according to the classical numbering system [3,4]. Metformin with insulin was initiated, but insulin therapy was discontinued because of frequent hypoglycemia. Continued metformin treatment with adequate diet and exercise improved her HbA1c level to 6.8%.

The patient's mother carried the same mutation and also did not present with AN or menstruation abnormalities. She was similarly nonobese (BMI, 16.38 kg/m2) and had a history of gestational diabetes that required insulin treatment during her pregnancies. Her diabetes improved after delivery. She had no diabetes-related symptoms; however, her fasting blood glucose was 100ŌĆō150 mg/dL, and her postprandial blood glucose was Ōēź200 mg/dL, for which she started taking diabetes medications.

There is a diversity of clinical phenotypes, even with the same type of mutation at the same site in the INSR gene [5-7]. It is presumed that many such patients are overlooked. Type A IRS is diagnosed more often in women than in men because women have more frequent symptoms associated with hyperandrogenism. In the prediabetic phase, males exhibit only AN and sometimes hypoglycemia, and they often remain undiagnosed even after the development of symptomatic diabetes. Instead, this form of diabetes is probably diagnosed as type 2 diabetes in midlife [1,2]. In women, the features of type A IRS often do not become apparent until puberty or later. Type A IRS is not usually diagnosed during childhood [1,2]. Only a few cases of childhood diagnoses without common clinical features have been reported [8,9].

In those with severe insulin resistance, puberty is often accelerated, most likely due to the action of hyperinsulinemia, which exerts synergistic effects with gonadotropins on the ovaries [1,2]. However, no cases of type A IRS with precocious puberty have been reported. Although the patient in this study was treated for central precocious puberty, her mother, who had the same mutation, did not experience precocious puberty or menstrual abnormalities. Therefore, we could not conclude that the insulin resistance of this patient was related to CPP.

In our study, the patient did not exhibit dyslipidemia. The absence of dyslipidemia and fatty liver disease as well as inappropriately normal or elevated plasma adiponectin level are characteristic clinical features in patients with severe insulin resistance due to mutation in INSR [1,2].

Although metformin has limited efficacy, it should be introduced early if severe hyperinsulinemia persists, and it can be beneficial at high doses. As diabetes progresses, patients whose condition is not controlled by oral hypoglycemic agents may require high doses of exogenous insulin and may show limited effect. Long-term metabolic control has been reported to be poor, and diabetes complications are frequent in patients with type A IRS [10].

Notes

Fig.┬Ā1.

Sequencing results for a mutation in the INSR gene of the patient and her parents. A heterozygous G to A transition at nucleotide 3602 of the INSR gene (c.3602G>A) resulting in a missense replacement of arginine with glutamine at amino acid 1201 (p.Arg1201Gln) was identified in the proband and mother but not in her father.

Table┬Ā1.

Levels of HbA1c, insulin, and sex hormones during follow-up

| Age (yr) | HbA1c (%) | F-glc (mg/dL) | C-peptide (ng/mL) | F-ins (╬╝lU/mL) | T-chol (mg/dL) | TG (mg/dL) | LH (mIU/mL) | FSH (mIU/mL) | T (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14* | 10.6 | 179 | 1.8 | 34.8 | 160 | - | 2.8 | 7.8 | 0.2 |

| 14.5 | 6.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15.3 | 8.1 | 137 | 1.9 | 26.5 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 0.26 | ||

| 15.8 | 8.1 | 150 | 1.5 | 35.8 | 129 | 44 | 8.3 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| 16 | 7.1 | 132 | 1.7 | 32.7 | 114 | 37 | - | - | - |

| 16.5 | 7 | 120 | 1.4 | 23.9 | 128 | 51 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 0.38 |

References

1. Parker VE, Semple RK. Genetics in endocrinology: genetic forms of severe insulin resistance: what endocrinologists should know. Eur J Endocrinol 2013;169:R71ŌĆō80.

2. Semple RK, Savage DB, Cochran EK, Gorden P, OŌĆÖRahilly S. Genetic syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Endocr Rev 2011;32:498ŌĆō514.

3. Moller DE, Cohen O, Yamaguchi Y, Assiz R, Grigorescu F, Eberle A, et al. Prevalence of mutations in the insulin receptor gene in subjects with features of the type A syndrome of insulin resistance. Diabetes 1994;43:247ŌĆō55.

4. Moritz W, Froesch ER, Boni-Schnetzler M. Functional properties of a heterozygous mutation (Arg1174Gln) in the tyrosine kinase domain of the insulin receptor from a type A insulin resistant patient. FEBS Lett 1994;351:276ŌĆō80.

5. Preumont V, Feincoeur C, Lascols O, Courtillot C, Touraine P, Maiter D, et al. Hypoglycemia revealing heterozygous insulin receptor mutations. Diabetes Metab 2017;43:95ŌĆō6.

6. Takahashi I, Yamada Y, Kadowaki H, Horikoshi M, Kadowaki T, Narita T, et al. Phenotypical variety of insulin resistance in a family with a novel mutation of the insulin receptor gene. Endocr J 2010;57:509ŌĆō16.

7. Dom├Łnguez-Garc├Ła A, Mart├Łnez R, Urrutia I, Garin I, Casta├▒o L. Identification of a novel insulin receptor gene heterozygous mutation in a patient with type A insulin resistance syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2014;27:561ŌĆō4.

8. Wei C, Burren CP. Diagnostic and management challenges from childhood, puberty through to transition in severe insulin resistance due to insulin receptor mutations. Pediatr Diabetes 2017;18:835ŌĆō38.