|

|

- Search

| Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab > Volume 18(3); 2013 > Article |

Abstract

Neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM) is a rare disease requiring insulin treatment. Its treatment is primarily focused on maintaining adequate glycemic control and avoiding hypoglycemia. Although insulin pump therapy is frequently administered to adults and children, there is no consensus on the use of insulin pumps in NDM. A 10 day-old female infant was referred to us with intrauterine growth retardation and poor weight gain. Hyperglycemia was noted, and continuous intravenous insulin infusion was initiated. However, the patient's serum glucose levels fluctuated widely, and maintaining the intravenous route became difficult within the following weeks. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion with an insulin pump was introduced on the twenty-fifth day of life, and good glycemic control was achieved without any notable adverse effects including hypoglycemia. We suggest that the insulin pump is a safe and effective mode for treating NDM and its early adoption may shorten the length of hospital stays in patients with NDM.

Neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM) is a rare (1:400,000 newborns) disease defined as hyperglycemia occurring within the first month of life that requires exogenous insulin and persists more than 2 weeks1). There are two forms of NDM, transient NDM (TNDM) and permanent NDM (PNDM). TNDM, accounting for about 50-60% of NDM, recovers by 18 months of age2).

Insulin therapy is crucial in NDM to obtain satisfactory weight gain and catch-up growth, especially because many of these newborns exhibit intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR)2). Avoiding hypoglycemia is another important goal because recurrent hypoglycemia at this age may result in neurodevelopmental sequelae3).

However, data on the treatment of NDM, especially on the mode of insulin delivery, are very limited. Continuous intravenous insulin infusion is the preferred initial treatment, but long-term installation of an intravenous line is often intolerable in newborns with IUGR. Intermittent subcutaneous insulin injection is often tried, but hypoglycemia is frequent and sometimes inevitable2).

A female infant was born at 38 weeks of gestation weighing 2,060 g (<3rd percentile) without any gestational complications. She was referred to our neonatal intensive care unit on the 10th day of life because of poor weight gain.

On admission, she weighed 1,920 g with a length of 43 cm (<3rd percentile), and a head circumference of 33 cm (25th percentile). There was no abnormal finding on physical and neurologic examinations. There was no evidence of hepatic/renal dysfunction or exocrine pancreas insufficiency.

Her initial serum glucose level was 160 mg/dL. The next morning, her blood glucose measured 557 mg/dL and urine contained 4+ glucose without ketone. Her serum C-peptide concentration was 0.45 ng/mL and insulin was 1.53 ┬ĄU/mL. Antibodies for glutamic acid decarboxylase and islet cells were both negative.

Continuous intravenous insulin infusion was started, with regular insulin diluted in a 1:100 mixture with normal saline, and the patient started to gain weight. Target blood glucose was 100 to 360 mg/dL. Blood glucose was monitored every 3 hours. When hypoglycemia was noted, 2 mL/kg of 10% glucose solution was given intravenously, and blood glucose was checked after 30 minutes. The rate of insulin infusion was titrated according to blood glucose, and it was maintained between 0.016 and 0.03 U/kg/hr. However, the glucose levels fluctuated widely, and maintaining an intravenous route became difficult within the following weeks.

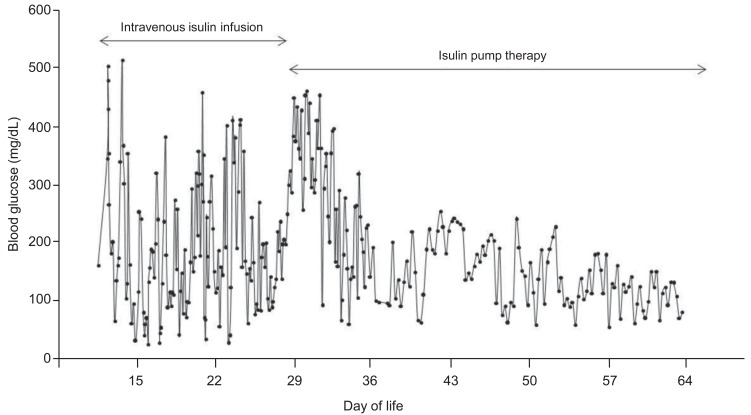

On the 25th day of life, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) with an insulin pump was commenced. Insulin lispro (Humalog, Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was administered in a 1:10 dilution at an initial basal rate of 0.016 U/kg/hr, according to the most recent dose of intravenous infusion. Hyperglycemia was still frequent during the first week of CSII, but hypoglycemic episodes disappeared after the adoption of insulin pump therapy. The basal rate of CSII was maintained between 0.021 to 0.023 U/kg/hr without meal bolus. Stable glycemic control was achieved within one week as the insulin pump settings were optimized (Fig. 1). The patient was transferred to a general ward, and her parents were educated about insulin pump therapy. The patient was discharged on the 38th day of life, weighing 3,180 g. Molecular analysis revealed paternal disomy of chromosome 6, suggesting TNDM (Fig. 2). She did not have activating mutations of KCNJ11 gene.

The insulin was gradually reduced over the following months. At 4 months of age, she weighed 6.7 kg; her glycosylated hemoglobin was 5.3% and C-peptide level was 1.09 ng/mL. There were no significant cutaneous or systemic complications associated with insulin pump therapy. Insulin was discontinued at 5 months of age. At 7 months of age, she weighed 8.0 kg (25-50th percentile) with a height of 68 cm (50th percentile).

The clinical features of TNDM include severe IUGR, hyperglycemia that begins in the neonatal period and resolves by age 18 months, dehydration, and absence of ketoacidosis. Because the plasma concentration of insulin is low at the time of diagnosis, it is assumed that low birth weight is a result of low in utero levels of insulin, an important prenatal growth factor6). Although the prognoses may differ, TNDM cannot be distinguished from PNDM based on clinical features because considerable overlap exists between them2).

Genetic testing provides a useful tool for identifying TNDM from PNDM. Genetic mutations such as activating mutations in the KCNJ11 gene encoding Kir6.2 subunit or in the ABCC8 encoding SUR1 subunit of the pancreatic KATP channel, were reported to be associated with PNDM7-9). These mutations result in overactive channels, leading to hyperpolarization of ╬▓ cells and reduced insulin secretion. On the other hand, abnormalities in chromosome 6 including paternal uniparental disomy and duplication of 6q24 on the paternal allele have been demonstrated in patients with TNDM2,10,11). Overexpression of imprinted genes at 6q24 (PLAGL1 and HYMAI) has been reported to result in TNDM6). Our patient had paternal disomy of chromosome 6, which predicts TNDM, and went into remission at 5 months of age.

Treatment of NDM has been primarily focused on maintenance of stable glucose levels and avoidance of hypoglycemia. Intravenous insulin infusion remains the first-line strategy in NDM to achieve satisfactory glycemic control in a titratable manner4). However, long-term intravenous access in newborns with IUGR is very complicated, and requires prolonged hospitalization.

Intermittent subcutaneous insulin injection is also a conventional approach for treatment of NDM. Subcutaneous injection of intermediate-acting insulin twice a day is no longer recommended in NDM because it frequently induces hypoglycemia2). Long-acting basal insulin potentially provides background insulin requirements, but has not yet been approved for neonates in most countries2). The management of hypoglycemic episodes may be complicated by these agents because their effects persist for more than 20 hours after injection. Furthermore, absorption of subcutaneously injected insulin is unpredictable in newborns with little subcutaneous fat, especially when the condition is associated with IUGR12).

Insulin pump therapy allows for minute changes of dosage with meals during the day. The insulin pump can deliver small doses of insulin, about 0.05 units at a time; whereas the smallest insulin dose that can be accurately administered without dilution using a syringe is 0.5 units. The efficacy of insulin pump therapy has been well established in adult practice13). It is also considered a safe and well-accepted method for pediatric diabetes14,15). Some researchers have described the safety and efficacy of CSII in NDM4,5,16). However, there is no consensus on the use of insulin pump for NDM, and it is not widely used in clinical practice for treatment of NDM.

In this case, we introduced insulin pump therapy for the treatment of a newborn with TNDM. The patient's glucose levels were soon stabilized without hypoglycemia. The excellent glycemic control obtained after CSII may not be solely due to the use of an insulin pump. It is also possible that the infant, whose condition appeared to be transient NDM, was already in the recovery phase of beta cell function.

We conclude that insulin pump therapy is a safe and effective mode of treatment for NDM. Early adoption of insulin pump therapy for NDM may also shorten the length of hospital stays.

References

1. von M├╝hlendahl KE, Herkenhoff H. Long-term course of neonatal diabetes. N Engl J Med 1995;333:704ŌĆō708. PMID: 7637748.

2. Polak M, Cave H. Neonatal diabetes mellitus: a disease linked to multiple mechanisms. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2:12. PMID: 17349054.

3. Burns CM, Rutherford MA, Boardman JP, Cowan FM. Patterns of cerebral injury and neurodevelopmental outcomes after symptomatic neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics 2008;122:65ŌĆō74. PMID: 18595988.

4. Bharucha T, Brown J, McDonnell C, Gebert R, McDougall P, Cameron F, et al. Neonatal diabetes mellitus: Insulin pump as an alternative management strategy. J Paediatr Child Health 2005;41:522ŌĆō526. PMID: 16150072.

5. Wintergerst KA, Hargadon S, Hsiang HY. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in neonatal diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes 2004;5:202ŌĆō206. PMID: 15601363.

6. Temple IK, Mackay DJ, Docherty LE. Diabetes mellitus, 6q24-related transient neonatal. Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Stephens Ket al., editors. GeneReviewsŌäó [monograph on the Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. 2005;10;updated 2012 Sep 27. cited 2013 Sep 10. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20301706.

7. Gloyn AL, Pearson ER, Antcliff JF, Proks P, Bruining GJ, Slingerland AS, et al. Activating mutations in the gene encoding the ATP-sensitive potassium-channel subunit Kir6.2 and permanent neonatal diabetes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1838ŌĆō1849. PMID: 15115830.

8. Vaxillaire M, Populaire C, Busiah K, Cave H, Gloyn AL, Hattersley AT, et al. Kir6.2 mutations are a common cause of permanent neonatal diabetes in a large cohort of French patients. Diabetes 2004;53:2719ŌĆō2722. PMID: 15448107.

9. Babenko AP, Polak M, Cave H, Busiah K, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R, et al. Activating mutations in the ABCC8 gene in neonatal diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2006;355:456ŌĆō466. PMID: 16885549.

10. Temple IK, Shield JP. Transient neonatal diabetes, a disorder of imprinting. J Med Genet 2002;39:872ŌĆō875. PMID: 12471198.

11. Docherty LE, Poole RL, Mattocks CJ, Lehmann A, Temple IK, Mackay DJ. Further refinement of the critical minimal genetic region for the imprinting disorder 6q24 transient neonatal diabetes. Diabetologia 2010;53:2347ŌĆō2351. PMID: 20668833.

12. Sindelka G, Heinemann L, Berger M, Frenck W, Chantelau E. Effect of insulin concentration, subcutaneous fat thickness and skin temperature on subcutaneous insulin absorption in healthy subjects. Diabetologia 1994;37:377ŌĆō380. PMID: 8063038.

13. Mecklenburg RS, Benson EA, Benson JW Jr, Blumenstein BA, Fredlund PN, Guinn TS, et al. Long-term metabolic control with insulin pump therapy: report of experience with 127 patients. N Engl J Med 1985;313:465ŌĆō468. PMID: 4022079.

14. Shalitin S, Phillip M. The use of insulin pump therapy in the pediatric age group. Horm Res 2008;70:14ŌĆō21. PMID: 18493145.

15. Weinzimer SA, Swan KL, Sikes KA, Ahern JH. Emerging evidence for the use of insulin pump therapy in infants, toddlers, and preschool-aged children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2006;7(Suppl 4):15ŌĆō19. PMID: 16774613.

16. Tubiana-Rufi N. Insulin pump therapy in neonatal diabetes. Endocr Dev 2007;12:67ŌĆō74. PMID: 17923770.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 6 Crossref

- 8,183 View

- 131 Download

- Related articles in APEM

-

Stem Cell Therapy for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus.2012 June;17(2)

Insulin Self-injection in School by Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus.2012 December;17(4)

Insulin Therapy in Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus.1999 December;4(2)

Leptin Levels in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus.2000 June;5(1)