|

|

- Search

| Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab > Volume 27(2); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Skeletal dysplasia is a diverse group of disorders that affect bone development and morphology. Currently, approximately 461 different genetic skeletal disorders have been identified, with over 430 causative genes. Among these, fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3)-related skeletal dysplasia is a relatively common subgroup of skeletal dysplasia. Pediatric endocrinologists may encounter a suspected case of skeletal dysplasia in their practice, especially when evaluating children with short stature. Early and accurate diagnosis of FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasia is essential for timely management of complications and genetic counseling. This review summarizes 5 representative and distinct entities of skeletal dysplasia caused by pathogenic variants in FGFR3 and discusses emerging therapies for FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias.

· Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3)-related skeletal dysplasia is a relatively common disease entity. Early diagnosis is essential for timely management of complications. Emerging targeted therapies are expected to provide better outcomes in these patients in the near future.

Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and FGF receptors (FGFRs) play essential roles in human axial and craniofacial skeletal development. FGFR3 inhibits chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation and promotes chondrocyte apoptosis [1]. Consequently, pathogenic variants of the FGFR3 gene, which mostly exhibit gain-of-function, are responsible for a group of chondrodysplasias characterized by short-limb dwarfism, macrocephaly, and a narrow thorax. Since the discovery of the activating FGFR3 variant as the genetic cause of achondroplasia (ACH) in 1994, other disorders caused by gain-of-function FGFR3 variants have been elucidated. These include hypochondroplasia (HCH), thanatophoric dysplasia types 1 (TD1) and 2 (TD2), and severe ACH with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans (SADDAN) [2]. Camptodactyly, tall stature, scoliosis, and hearing loss (CATSHL) syndrome has been reported in 2 families, showing excessive skeletal growth due to loss-of-function of FGFR3 [3,4]. The appropriate diagnosis of FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias depends on the combination of family history, clinical and radiologic findings, and molecular tests [5]. To date, treatment of skeletal dysplasias has been largely supportive, including skeletal surgery. However, in recent decades, several therapeutic strategies targeting the FGFR3 signaling pathway have been investigated. The first drug, vosoritide, was approved and is currently used in the United States and Europe [2,6,7]. In this review, we describe the clinico-radiologic and molecular findings of FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasia, and discuss recent therapeutic achievements, focusing on pharmacological approaches in ACH.

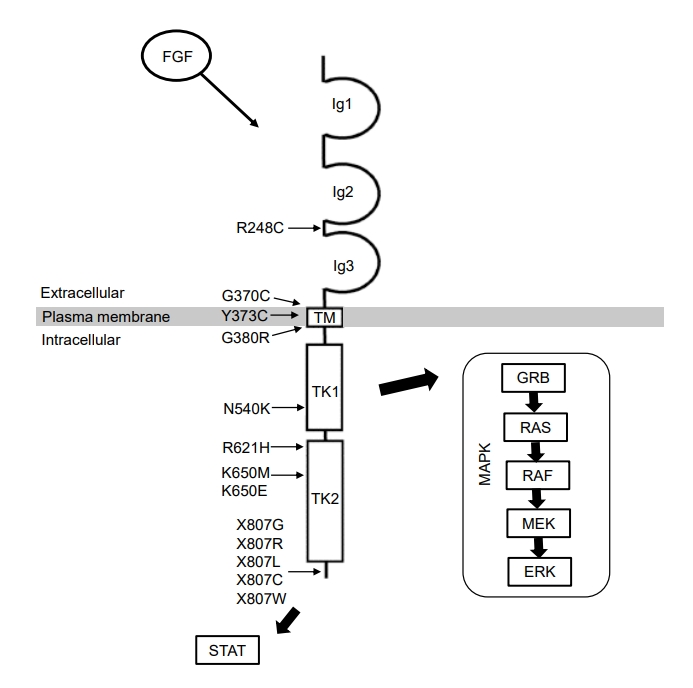

FGFR3 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that comprises an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane domain, and 2 intracellular tyrosine kinase domains [8]. Binding of various FGFs to FGFR3 induces receptor dimerization and transphosphorylation of tyrosine residues [9], leading to activation of several downstream signaling pathways, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (Fig. 1) [10,11]. Gain-of-function variants in the FGFR3 gene lead to increased signal transduction of FGFR3, thus suppressing chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation [12]. This impairs endochondral ossification of long bones, leading to poor extension of the long bones. Loss of FGFR3 function induces overgrowth of long bones in mice with knockout variants of FGFR3 and individuals with CATSHL syndrome [3,10,13,14], which supports the important role of FGFR3 as a negative regulator of bone growth.

Diagnosis of FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasia is established based on clinical and radiological findings and/or identification of FGFR3 pathogenic variants (Table 1). Radiological evaluation with a complete skeletal survey plays a crucial role in the diagnostic workup of skeletal dysplasia. Radiographic survey includes the skull, spine, chest, pelvis, legs, arms, and hands (Table 2) [15].

ACH (MIM 100800) is the most common cause of short-limb dwarfism and affects more than 250,000 people worldwide [16]. Estimated prevalence ranges from 0.4–0.6 per 10,000 live births [17]. ACH follows an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, with more than 80% of cases attributable to spontaneous mutation [16]. The increased incidence of sporadic cases is partially associated with advanced paternal age [18]. Virtually all patients carry the 2 common pathogenic variants of the FGFR3 gene (c.1138G>A and c.1138G>C), which results in identical mutant proteins, p.Gly380Arg (G380R) [19]. The diagnosis can easily be made in early infancy based on physical and radiological features. The clinical features include rhizomelic shortening of the limbs, distinctive facial features (frontal bossing, depressed nasal bridge, and midface hypoplasia), macrocephaly, brachydactyly, and trident hands. Other reported associations include foramen magnum narrowing, ventricular enlargement, obstructive sleep apnea, a narrow thorax, upper airway stenosis, spinal stenosis, genu varum, limited elbow extension, and joint hyperextensibility (especially of the knees) [20-22]. In the United States, the mean adult height is approximately 131±5.6 cm for men and 124±5.9 cm for women [23]. Intelligence and lifespan are usually in the normal range, although brainstem compression increases the risk of unexpected infant death [24]. Specific features on radiographs include rhizomelic shortening of the long bones with metaphyseal flaring, shortened femoral necks, proximal femoral radiolucency, chevron shape of the distal femoral epiphyses, relatively long fibula bones compared to tibia bones, short and broad pelvis with horizontal acetabuli and squaring of iliac wings, and short pedicles of the vertebrae with caudal narrowing of the lumbar interpedicular distance [5,25]. Although molecular confirmation is not generally needed to diagnose ACH in individuals with typical findings, molecular analysis may aid in establishing a diagnosis in those with atypical presentations or receiving new treatments.

HCH (MIM 146000) is the mildest form of FGFR3-related dwarfism, and its expected prevalence is similar to that of ACH. HCH is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner, with the majority of new cases caused by de novo variants in the FGFR3 gene, which have been associated with advanced paternal age [26]. Approximately 70% of patients are heterozygous for the 2 recurrent variants of FGFR3 (c.1620C>A and c.1620C>G), causing identical amino acid changes of p.Asn540Lys (N540K) in its tyrosine kinase domain [27-29]. HCH diagnosis is challenging because of the subtle clinico-radiologic features and phenotypic overlap with other skeletal dysplasias. There is a wide spectrum of clinical severities, and clinical features may become apparent over time. Patients usually present with short stature with mild limb shortening, macrocephaly, lumbar lordosis, and brachydactyly [30]. In South America, mean adult height was reported to be 143.6 cm (range, 131–154.5 cm) for men and 130.8 cm (range, 124–138 cm) for women [31]. Although the medical complications prevalent in ACH (e.g., spinal stenosis) are less frequent [32], intellectual disabilities and seizures may be more common in HCH [33,34]. The skeletal features of HCH are similar to those in ACH but are much milder. Because there is no consensus on the clinical diagnosis of HCH, molecular confirmation is necessary to distinguish HCH from other skeletal dysplasias in patients with overlapping phenotypes.

TD is the most common lethal skeletal dysplasia, with a reported incidence of 0.2 to 0.5 per 10,000 live births [35]. TD is typically caused by de novo pathogenic FGFR3 variants, which have been associated with an advanced paternal age effect [36]. The clinical and radiographic features of TD are evident prenatally or immediately after birth. These include micromelia, macrocephaly, distinctive facial features (frontal bossing and a depressed nasal bridge), and a narrow thorax. There are 2 clinical types of TD: type 1 (TD1, MIM 187600) and type 2 (TD2, MIM 187601). The characteristic bowed femurs in TD1 may distinguish it from TD2. TD2 is characterized by severe craniosynostosis with cloverleaf skull deformity, which is rarely seen in TD1 [37]. Most affected individuals die in the perinatal period from respiratory failure due to narrow thorax, lung hypoplasia, and/or compression of the brainstem due to narrowing of the foramen magnum [38]. Neonates typically require long-term respiratory support to survive. Rare long-term survivors have been reported, who are often ventilatordependent, with marked growth deficiency and extreme intellectual disability [39-44].

SADDAN (MIM 616482) is a rare skeletal dysplasia caused by a heterozygous FGFR3 pathogenic variant (c.1949A>T) that results in amino acid changes in p.Lys650Met (K650M) [45,46]. The clinical features include extremely short stature, macrocephaly, characteristic facial features (frontal bossing, depressed nasal bridge, and midface hypoplasia), rhizomelic or mesomelic limb shortening, severe tibial bowing, seizures, developmental delay, and acanthosis nigricans. The clinical features overlap with those of TD, however, individuals with SADDAN often survive beyond infancy without ventilatory support. However, early mortality with respiratory failure has been reported, and respiratory support may be needed during the neonatal period [45-47].

CATSHL syndrome (MIM 610474) is a distinct skeletal dysplasia caused by loss of FGFR3 function [3]. Since its first description in 1996, 2 families with CATSHL syndrome have been reported, one with a heterozygous variant and the other with a homozygous variant [3,4]. The c.1915G>A variant in the FGFR3 gene results in an amino acid change in p.Arg621His (p.R621H) that induces loss-of-function of the gene. Major features included camptodactyly, tall stature (mean adult height of 195.6 cm in men and 177.8 cm in women), and hearing loss. Other observed findings included kyphoscoliosis, a high palate, microcephaly, and intellectual disabilities.

Management of skeletal dysplasia is currently largely supportive, including periodic measurements of growth, surgery for craniocervical junction stenosis and hydrocephalus, management of middle ear infections and obstructive sleep apnea, and surgical intervention for spinal stenosis, thoracolumbar kyphosis, and leg bowing [22]. Other treatment interventions may include antiseizure medications, hearing aids, and individualized developmental support. Treatment for short stature depends on parental concerns and expectations. Recombinant growth hormone (GH) does not appear to be effective in ACH, with an expected additional adult height of only about 3 cm (approved only in Japan) [48]. On the other hand, a meta-analysis of 113 children with HCH revealed a greater response to GH therapy in children with HCH with major catch-up growth after 12 months, and improvement in height remained constant until 36 months of GH treatment [49]. However, the ultimate success of GH treatment in HCH remains uncertain due to the lack of data on final adult height in GH-treated patients. Extended limb lengthening is controversial in both ACH and HCH because of the frequent and often serious complications [50]. It is recommended that this invasive procedure be postponed until the patient can make an informed decision. In 2021, the FDA approved a C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) analog, vosoritide, to increase height in ACH individuals aged ≥5 years whose epiphyses are not closed [51].

Cancer biology has inspired attempts to block FGFR3 because aberrant FGFR signaling is also implicated in various cancers, including bladder and cervical cancers [52]. Therapeutic strategies targeting bone tissue affected by gain-of-function FGFR3 variants inhibit various steps of the FGFR3 pathway, targeting the FGF ligand or the FGFR3 receptor, tyrosine kinase activity of FGFR3, and downstream signals. Several clinical trials are currently underway for FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias, mainly for ACH (Table 3).

CNP is expressed in proliferating and prehypertrophic chondrocytes and stimulates chondrocyte proliferation by inhibiting MAPK signaling at the RAF-1 level [53-55]. A randomized, double-blind, phase-III trial of vosoritide (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03197766) demonstrated an average increase of 1.6 cm/yr in annual growth velocity in up to 121 children with ACH aged 5 to <18 years [56]. Children who completed this trial will be followed to assess long-term efficacy and safety (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03424018). Currently, vosoritide (Voxzogo; BioMarin, San Rafael, CA, USA) is available for patients with ACH in Europe and the United States. Additionally, a phase-II, randomized, double-blind trial of vosoritide in infants and younger children with ACH (age range, 0 to <60 months) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03583697) was recently completed (results not yet published). A phase-II, randomized, open-label trial evaluating the safety of vosoritide in infants at risk for cervicomedullary decompression surgery is now recruiting participants aged 0–12 months (ClinicalTrials. gov identifier: NCT04554940). Another phase-II study of vosoritide (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04219007) is ongoing in children 3–10 years of age with selected genetic causes of short stature, including HCH.

Another CNP derivative with a longer half-life that can be administered by weekly subcutaneous injection, has also been developed (TransCon CNP; Ascendis Pharma A/S, Hellerup, Denmark). A phase-I study has been completed, and an observational study to document the natural history is recruiting infants and children with ACH aged 0–8 years (ClinicalTrials. gov number, NCT03875534; ACHieve). Currently, children aged 2–10 years with ACH are being enrolled in phase-II, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trials to evaluate the safety and efficacy of TransCon CNP (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04085523; ACcomplisH, and NCT05246033; ACcomplisH China).

A soluble isoform of FGFR3 (TA-46, now called Recifercept) is currently in clinical development to treat children with ACH. It is composed of the extracellular domain of FGFR3 and acts as a decoy receptor, which prevents FGF from binding to the mutated FGFR3 by competing for physiologic ligands (i.e., FGFs 9, 18). A phase-I study using Recifercept (Pfizer Ltd., New York, NY, USA) has been completed, and an observational study investigating baseline clinical characteristics of children with ACH aged 0–10 years (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03794609) has been conducted. Currently, 2 phase-II studies to document the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of Recifercept are recruiting children with ACH aged 3 months to 10 years (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04638153), and aged 15 months to 12 years (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT05116046).

Infigratinib (NVP-BGJ398), an orally bioavailable and selective FGFR1-3 selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, counteracts the hyperactivity of FGFR3 by inhibiting phosphorylation of FGFR, resulting in attenuation of its downstream signaling [57]. Phase-I studies using this tyrosine kinase inhibitor (infigratinib; QED therapeutics) have been completed, and an observational study to evaluate its natural history has commenced in children with ACH aged 30 months to 10 years (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04035811; PROPEL). A phase-II study evaluating the safety and efficacy of infigratinib (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04265651; PROPEL 2) is recruiting children with ACH aged 3–11 years. Additionally, a phase-II, multicenter, open-label extension (OLE) study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT05145010; PROPEL OLE) is ongoing to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of infigratinib in children aged 3–18 years with ACH.

Meclozine, an antihistamine that has long been used to treat motion sickness, was considered a putative treatment because it downregulates phosphorylation of ERK in the MAPK pathway. In a preclinical study, oral administration of meclozine significantly increased the length of long bones in transgenic ACH mouse pups [58]. Additionally, a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs, statins, rescued cartilage degradation in patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell models and led to a significant recovery of bone growth in transgenic ACH mouse pups [59]. However, further experiments beyond animal models have not been conducted on either meclozine and statins.

FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias are a dynamic group of disorders with evolving skeletal phenotypes throughout the lives of affected individuals. Although some disorders are perinatally lethal, others have a relatively normal life expectancy. Early diagnosis is crucial for appropriate genetic counseling and prevention of serious medical complications through multidisciplinary care. With the advent of several therapeutic options targeting FGFR3 in ACH, these new therapies are expected to be effective in other FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias. Hopefully, they will provide better, nonsurgical options for these patients to improve their quality of life and minimize medical complications.

Notes

Fig. 1.

Human FGFR3 protein structure and FGFR3 signal transduction. Positions of the representative pathogenic variants in the FGFR3 gene are indicated. Ig, immunoglobulin-like domain; TM, transmembrane domain; TK, tyrosine kinase domain; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; MAPK, mitogen activated protein kinase.

Table 1.

Key features of FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias

OMIM, On line Mendelian Inheritance in Man; ACH, achondroplasia; AD, autosomal dominant; HCH, hypochondroplasia; TD, thanatophoric dysplasia; SADDAN, severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans; CATSHIL, camptodactyly, tall stature, scoliosis, and hearing loss; AR, autosomal recessive.

Table 2.

A complete set of radiographs in a skeletal survey [15]

Table 3.

Ongoing clinical trials in FGFR3-related skeletal dysplasias

References

1. Du X, Xie Y, Xian CJ, Chen L. Role of FGFs/FGFRs in skeletal development and bone regeneration. J Cell Physiol 2012;227:3731–43.

2. Foldynova-Trantirkova S, Wilcox WR, Krejci P. Sixteen years and counting: the current understanding of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) signaling in skeletal dysplasias. Hum Mutat 2012;33:29–41.

3. Toydemir RM, Brassington AE, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Krakowiak PA, Jorde LB, Whitby FG, et al. A novel mutation in FGFR3 causes camptodactyly, tall stature, and hearing loss (CATSHL) syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:935–41.

4. Makrythanasis P, Temtamy S, Aglan MS, Otaify GA, Hamamy H, Antonarakis SE. A novel homozygous mutation in FGFR3 causes tall stature, severe lateral tibial deviation, scoliosis, hearing impairment, camptodactyly, and arachnodactyly. Hum Mutat 2014;35:959–63.

5. Sargar KM, Singh AK, Kao SC. Imaging of skeletal disorders caused by fibroblast growth factor receptor gene mutations. Radiographics 2017;37:1813–30.

6. Marzin P, Cormier-Daire V. New perspectives on the treatment of skeletal dysplasia. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2020;11:2042018820904016.

7. Legeai-Mallet L, Savarirayan R. Novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of achondroplasia. Bone 2020;141:115579.

8. Laederich MB, Horton WA. Achondroplasia: pathogenesis and implications for future treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010;22:516–23.

10. Deng C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Zhou F, Kuo A, Leder P. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Cell 1996;84:911–21.

11. Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2005;16:139–49.

12. Segev O, Chumakov I, Nevo Z, Givol D, Madar-Shapiro L, Sheinin Y, et al. Restrained chondrocyte proliferation and maturation with abnormal growth plate vascularization and ossification in human FGFR-3(G380R) transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 2000;9:249–58.

13. Colvin JS, Bohne BA, Harding GW, McEwen DG, Ornitz DM. Skeletal overgrowth and deafness in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat Genet 1996;12:390–7.

14. Escobar LF, Tucker M, Bamshad M. A second family with CATSHL syndrome: confirmator y report of another unique FGFR3 syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2016;170:1908–11.

15. Offiah AC, Hall CM. Radiological diagnosis of the constitutional disorders of bone. As easy as A, B, C? Pediatr Radiol 2003;33:153–61.

17. Waller DK, Correa A, Vo TM, Wang Y, Hobbs C, Langlois PH, et al. The population-based prevalence of achondroplasia and thanatophoric dysplasia in selected regions of the US. Am J Med Genet A 2008;146A:2385–9.

18. Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Scarano G, Mastroiacovo P. Effect of paternal age in achondroplasia, thanatophoric dysplasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Med Genet 1995;59:209–17.

19. Bellus GA, Hefferon TW, Ortiz de Luna RI, Hecht JT, Horton WA, Machado M, et al. Achondroplasia is defined by recurrent G380R mutations of FGFR3. Am J Hum Genet 1995;56:368–73.

20. Legare JM. Achondroplasia. Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, et al., editors. GeneReviews((R)). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. 1993-2022.

21. Kubota T, Adachi M, Kitaoka T, Hasegawa K, Ohata Y, Fujiwara M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for achondroplasia. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol 2020;29:25–42.

22. Hoover-Fong J, Scott CI, Jones MC, COMMITTEE ON GENETICS. Health supervision for people with achondroplasia. Pediatrics 2020;145:e20201010.

23. Horton WA, Rotter JI, Rimoin DL, Scott CI, Hall JG. Standard growth curves for achondroplasia. J Pediatr 1978;93:435–8.

24. Hecht JT, Francomano CA, Horton WA, Annegers JF. Mortality in achondroplasia. Am J Hum Genet 1987;41:454–64.

25. Panda A, Gamanagatti S, Jana M, Gupta AK. Skeletal dysplasias: a radiographic approach and review of common non-lethal skeletal dysplasias. World J Radiol 2014;6:808–25.

26. McKusick VA, Kelly TE, Dorst JP. Observations suggesting allelism of the achondroplasia and hypochondroplasia genes. J Med Genet 1973;10:11–6.

27. Prinos P, Costa T, Sommer A, Kilpatrick MW, Tsipouras P. A common FGFR3 gene mutation in hypochondroplasia. Hum Mol Genet 1995;4:2097–101.

28. Rousseau F, Bonaventure J, Legeai-Mallet L, Schmidt H, Weissenbach J, Maroteaux P, et al. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity of hypochondroplasia. J Med Genet 1996;33:749–52.

29. Xue Y, Sun A, Mekikian PB, Martin J, Rimoin DL, Lachman RS, et al. FGFR3 mutation frequency in 324 cases from the International Skeletal Dysplasia Registry. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2014;2:497–503.

31. Arenas MA, Del Pino M, Fano V. FGFR3-related hypochondroplasia: longitudinal growth in 57 children with the p.Asn540Lys mutation. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2018;31:1279–84.

32. Wynne-Davies R, Walsh WK, Gormley J. Achondroplasia and hypochondroplasia. Clinical variation and spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1981;63B:508–15.

33. Wynne-Davies R, Patton MA. The frequency of mental retardation in hypochondroplasia. J Med Genet 1991;28:644.

34. Linnankivi T, Makitie O, Valanne L, Toiviainen-Salo S. Neuroimaging and neurological findings in patients with hypochondroplasia and FGFR3 N540K mutation. Am J Med Genet A 2012;158A:3119–25.

35. Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Barbosa-Neto JG. The birth prevalence rates for the skeletal dysplasias. J Med Genet 1986;23:328–32.

36. Donnelly DE, McConnell V, Paterson A, Morrison PJ. The prevalence of thanatophoric dysplasia and lethal osteogenesis imperfecta type II in Northern Ireland - a complete population study. Ulster Med J 2010;79:114–8.

37. French T, Savarirayan R. Thanatophoric dysplasia. 2004 May 21 [updated 2020 Jun 18. Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya Aet al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. 1993-2022.

39. MacDonald IM, Hunter AG, MacLeod PM, MacMurray SB. Growth and development in thanatophoric dysplasia. Am J Med Genet 1989;33:508–12.

40. Nikkel SM, Major N, King WJ. Growth and development in thanatophoric dysplasia - an update 25 years later. Clin Case Rep 2013;1:75–8.

41. Baker KM, Olson DS, Harding CO, Pauli RM. Long-term survival in typical thanatophoric dysplasia type 1. Am J Med Genet 1997;70:427–36.

42. Nakai K, Yoneda K, Moriue T, Munehiro A, Fujita N, Moriue J, et al. Seborrhoeic keratoses and acanthosis nigricans in a long-term survivor of thanatophoric dysplasia. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:656–8.

43. Katsumata N, Kuno T, Miyazaki S, Mikami S, Nagashima-Miyokawa A, Nimura A, et al. G370C mutation in the FGFR3 gene in a Japanese patient with thanatophoric dysplasia. Endocr J 1998;45 Suppl:S171–4.

44. Kuno T, Fujita I, Miyazaki S, Katsumata N. Markers for bone metabolism in a long-lived case of thanatophoric dysplasia. Endocr J 2000;47 Suppl:S141–4.

45. Tavormina PL, Bellus GA, Webster MK, Bamshad MJ, Fraley AE, McIntosh I, et al. A novel skeletal dysplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans is caused by a Lys650Met mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene. Am J Hum Genet 1999;64:722–31.

46. Zankl A, Elakis G, Susman RD, Inglis G, Gardener G, Buckley MF, et al. Prenatal and postnatal presentation of severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans (SADDAN) due to the FGFR3 Lys650Met mutation. Am J Med Genet A 2008;146A:212–8.

47. Bellus GA, Bamshad MJ, Przylepa KA, Dorst J, Lee RR, Hurko O, et al. Severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans (SADDAN): phenotypic analysis of a new skeletal dysplasia caused by a Lys650Met mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Am J Med Genet 1999;85:53–65.

48. Harada D, Namba N, Hanioka Y, Ueyama K, Sakamoto N, Nakano Y, et al. Final adult height in long-term growth hormone-treated achondroplasia patients. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:873–9.

49. Massart F, Miccoli M, Baggiani A, Bertelloni S. Height outcome of short children with hypochondroplasia after recombinant human growth hormone treatment: a meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics 2015;16:1965–73.

50. Ko KR, Shim JS, Chung CH, Kim JH. Surgical results of limb lengthening at the femur, tibia, and humerus in patients with achondroplasia. Clin Orthop Surg 2019;11:226–32.

51. Al Shaer D, Al Musaimi O, Albericio F, de la Torre BG. 2021 FDA TIDES (Peptides and Oligonucleotides) Harvest. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022;15:222.

52. Cappellen D, De Oliveira C, Ricol D, de Medina S, Bourdin J, Sastre-Garau X, et al. Frequent activating mutations of FGFR3 in human bladder and cervix carcinomas. Nat Genet 1999;23:18–20.

53. Krejci P, Masri B, Fontaine V, Mekikian PB, Weis M, Prats H, et al. Interaction of fibroblast growth factor and C-natriuretic peptide signaling in regulation of chondrocyte proliferation and extracellular matrix homeostasis. J Cell Sci 2005;118:5089–100.

54. Yasoda A, Komatsu Y, Chusho H, Miyazawa T, Ozasa A, Miura M, et al. Overexpression of CNP in chondrocytes rescues achondroplasia through a MAPK-dependent pathway. Nat Med 2004;10:80–6.

55. Suhasini M, Li H, Lohmann SM, Boss GR, Pilz RB. Cyclic-GMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits the Ras/Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18:6983–94.

56. Savarirayan R, Tofts L, Irving M, Wilcox W, Bacino CA, Hoover-Fong J, et al. Once-daily, subcutaneous vosoritide therapy in children with achondroplasia: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2020;396:684–92.

57. Unger S, Bonafe L, Gouze E. Current care and investigational therapies in achondroplasia. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2017;15:53–60.