New Korean reference for birth weight by gestational age and sex: data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (2008-2012)

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

To construct new Korean reference curves for birth weight by sex and gestational age using contemporary Korean birth weight data and to compare them with the Lubchenco and the 2010 United States (US) intrauterine growth curves.

Methods

Data of 2,336,727 newborns by the Korean Statistical Information Service (2008-2012) were used. Smoothed percentile curves were created by the Lambda Mu Sigma method using subsample of singleton. The new Korean reference curves were compared with the Lubchenco and the 2010 US intrauterine growth curves.

Results

Reference of the 3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 97th percentiles birth weight by gestational age were made using 2,249,804 (male, 1,159,070) singleton newborns with gestational age 23-43 weeks. Separate birth weight curves were constructed for male and female. The Korean reference curves are similar to the 2010 US intrauterine growth curves. However, the cutoff values for small for gestational age (<10th percentile) of the new Korean curves differed from those of the Lubchenco curves for each gestational age. The Lubchenco curves underestimated the percentage of infants who were born small for gestational age.

Conclusion

The new Korean reference curves for birth weight show a different pattern from the Lubchenco curves, which were made from white neonates more than 60 years ago. Further research on short-term and long-term health outcomes of small for gestational age babies based on the new Korean reference data is needed.

Introduction

Small for gestational age (SGA) means a developing fetus in the uterus or an infant is smaller in size than normal babie's adjusted for sex and gestational age (GA). It is commonly defined as a weight below the 10th percentile for the GA1). SGA must be differentiated from low birth weight due to prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Low birth weight is defined as an infant with a birth weight less than 2,500 g, regardless of GA at the time of birth. IUGR, also called "pathological SGA", refers to a condition in which a fetus is unable to achieve its genetically determined potential size.

Some infants born SGA, particularly with IUGR, suffer from acute and chronic consequences. They can suffer from perinatal event such as hypoglycemia, gastro-esophageal reflux, and hypothermia in neonatal period2,3) and, short stature without catch-up, premature adrenarche, and obesity in childhood4,5,6,7). Furthermore, SGA infants have significantly increased risk of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, polycystic ovarian syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) from children to adulthood3,8).

For a proper assessment and management of SGA, up-to-date ethnicity specific birth weight (or length) references by GA are needed9). Thus, many countries including United States (US) reported new birth weight or intrauterine growth references by sex and GA as old reference does not fit for contemporary population10,11,12,13,14,15). The new references and cut offs are useful for identifying children who have the risk of metabolic disease in the future.

The objectives of this study were: (1) to make the sex and GA specific birth weight reference data of Korean population and to develop new birth weight curves; (2) to compare these Korean specific birth weight curves with old but commonly used curves (the Lubchenco curves) and 2010 US intrauterine growth curves; and (3) to estimate the prevalence of SGA using new curves and Lubchenco curves.

Materials and methods

1. Study subjects

This study was performed using population data released by the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). The Korean National Statistic Office opened the KOSIS in July 2007 after establishing a statistical information database and building an integrated service system. It started under the national information strategy scheme in 2005. The KOSIS currently provides 343 types of statistics from domestic to international statistics produced by 87 organizations in Korea. In addition, KOSIS releases 100 major indicators of Korea, which provides information on current economic, social situations and health indicators, including birth and death rate data16). This study used 5-year (2008-2012) national birth data (a total of 2,336,727 newborns) provided by KOSIS, which are based on the birth registration for birth certificate. In the birth data set, birth place, birth order, twin or triplet, age of mother/father, sex, birth weight, and estimated GA were available. From this data, mean GA, mean birth weight, multiple pregnancy rate, and preterm, and postterm birth rates of Korean population were calculated.

2. Reference birth weight by GA

For the new Korean reference for birth weight by GA, we used data of singleton newborns. We made birth weight reference of male and female separately as birth size is different by sex. The GA was determined by rounding off. Thus, GA 36 weeks represents 36 weeks plus 0 to 6 days. We excluded data with missing weight (n=5,728); unknown sex; GA under 22 weeks (n=1,244), and over 44 weeks (n=173). Multiple births (n=67,396) were also excluded as it is well known to have negative impact on intrauterine growth. We further excluded "extreme outliers". Extreme outliers were defined as values >2 times the interquartile range (25th to 75th percentiles) below the first quartile and above the third quartile for each GA17). Thus, final analysis consisted 2,249,804 (male, 1,159,070) singleton newborns with GA between 23-43 weeks. The 3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 97th percentiles for male and female neonates were calculated.

3. Creation of curves

The percentile growth curves were created by using the Cole's Lambda Mu Sigma (LMS) method18). The LMS approach provides curves for mean weight and "standard deviation (SD) bands". These curves are not expected values and SDs of birth weight itself, but of a transformed value, a z-score. LMS approach initially estimates the three parameters of BOX-Cox transformation of the distribution of the measurement. The L determines a nonlinear transformation of birth weight, such that its distribution approximates the normal distribution. The M stands for the mean of that normal distribution, and S for its SD. The three parameters are constrained to change smoothly as the covariate changes. L, M, and S correspond to the following formulas: Z=[(X/M)L_1]/LS, where X indicates the measured value of birth weight; and centile=M (1+LSZ)1/L, where Z is the z-score that corresponds to a given percentile. Z-score is a measure of the distance in SDs of a sample from the mean. To create smoothed percentile charts for the 3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th and 97th percentiles, LMSChartMaker Pro 2.324 (Medical Research Council, London, UK) was used. Subsample of whole subjects was used as LMSChartMaker cover less than 100,000 data input.

4. Definition of SGA and comparison with other curves

By definition, 10% of a population should be <10th percentile (SGA), 80% between the 10th and 90th percentiles (appropriate for GA), and 10% >90th percentile (large for GA, LGA)1,10). We compared our new Korean reference curves for birth weight with new intrauterine growth curves published recently based on US data. We also compared ours with the Lubchenco curves as they are still commonly used in many countries including Korea for defining SGA.

5. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The data are presented as the mean±SD, percentile values for birth weight according to GA by sex. The new Korean reference curves for birth weight were generated by using LMS methods. The LMS parameters for the curves are also presented.

All drawings are made using GraphPad Prism ver. 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). As GA 36 weeks represent 36 weeks +0 day to +6 days in our data, we make reference curve to shift right by 0.5 weeks for comparison with other data.

Results

1. Subjects characteristics

The characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 1. The number of subjects in this study was 2,336,727 which cover the whole neonates born between 2008 and 2012 in Korea. The fathers' mean age of the entire subjects was 33.5±4.5 years (range, 14-75 years) and the mother's mean age was 30.7±4.0 years (range, 12-61 years). The mean GA for the entire subjects was 38.7 ±1.7 weeks (range, 16-49 weeks). The mean birth weight was 3,218±461 g. Female had lower birth weight than male (3,266±466 g vs. 3,168±451 g). The number of preterm neonates under 37 weeks of GA was 137,441 (5.9%) and the number of postterm neonates over 42 weeks of GA was 7,481 (0.3%).

2. Percentile distribution of birth weight by sex and GA

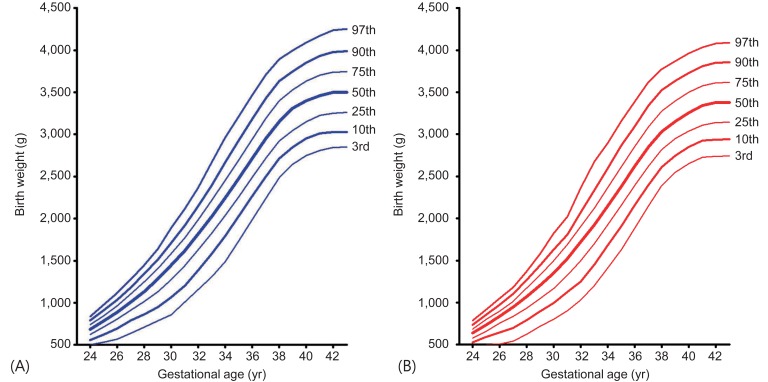

The mean and percentile birth weight of male newborns by GA are presented in Table 2 and those of female newborns in Table 3. Smoothed new Korean reference curves for birth weight of the 3th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 97th percentiles for male and female neonates are shown in Fig. 1. The LMS parameters for the curves are presented in Table 4. SGA is defined as birth weight <10th percentile for GA and LGA as birth weight >90th percentile for GA.

3. Comparison of new Korean reference curves for birth weight with the 2010 US intrauterine growth curves and Lubchenco curve

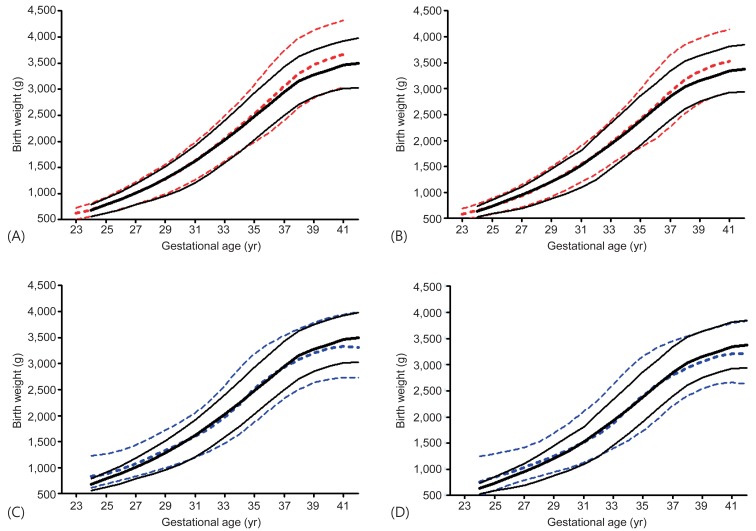

The new Korean reference curves for birth weight were plotted with the 2010 US intrauterine growth curves for comparison (Fig. 2A, B). Generally, the new Korean curves were similar to the 2010 US intrauterine growth curves until GA 36 weeks in both sexes. However, the Korean curves had lower average birth weight after GA 37 weeks. The 50th and 90th birth weight of Korean was lower after GA 37 weeks but 10th birth weight was similar to that of the US in both sexes.

The new Korean birth weight curves (black solid line) compared with the 2010 United States intrauterine growth curves (red dashed line) for male (A) and female (B) newborns/Lubchenco curves (blue dashed line) for male (C) and female (D) newborns. The line represents 10th, 50th, and 90th birth percentile, respectively.

The new Korean reference curves for birth weight were also plotted with the Lubchenco curves (Fig. 2C, D). Generally, the 90th percentile birth weight of Korean curves was lower than that of Lubchenco's in GA less than 36 weeks. However, the 90th percentile of GA over 37 weeks had birth weight slightly higher than that of Lubchenco's. The 50th birth weight of Korean population was lower until 30 weeks and higher after 37 weeks. The 10th birth weight cutoff of Korean curves was higher than the Lubchenco curves after 32 weeks in both sexes. Thus, the number of SGA in Korean population according to Lubchenco was smaller than that according to the new Korean reference cutoff. The prevalence of SGA according to <10th percentile of the Lubchenco curves was 1.92% (male, 1.90%; female, 1.95%), while the prevalence of SGA according to ≤3rd percentile and <10th percentile of the new Korean reference curves were 2.88% (male, 2.90%; female, 2.86%) and 9.56% (male, 9.43%; female, 9.70%), respectively. The prevalence of LGA (>90th percentile) according to the Lubchenco and the new Korean reference curves were 11.31% (male, 11.11%; female, 11.53%) and 9.79% (male, 9.76%; female, 9.82%), respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we developed the new Korean reference curves for birth weight by GA and sex based on the data of contemporary Korean infants. This new Korean birth weight data set and growth curves might be useful not only in assessing short-term health risks of SGA infants in neonatal intensivecare units but also in assessing long-term health risks such as short stature in childhood and metabolic risk in adulthood among children born SGA or LGA. Furthermore, possible misclassification of SGA infants using the Lubchenco curves, which was based on the old data of the US neonates and has commonly been used in Korea, supports the need for updated and Korean specific reference curves for birth weight.

1. The need for birth weight reference by GA and definition of SGA

Contemporary ethnicity specific birth weight references are needed to identify SGA infants who might suffer from acute and chronic consequences9). Some of SGA neonates are born following IUGR. Suboptimal fetal growth occurring in IUGR fetuses is an important cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity2,3). They suffer from hypoglycemia, anemia, hypothermia, respiratory distress, necrotizing enterocolitis, and retinopathy of prematurity, which contribute to perinatal morbidity. Furthermore, SGA children have significantly increased risks of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and CVD from children to adulthood3,8). In children and adolescents, they present endocrine sequelae, such as short stature, which persists into adults, premature adrenarche, and polycystic ovarian syndrome4,5,6,7). These sequelae can be prevented or managed if diagnosed early and appropriately. For example, growth hormone (GH) treatment for children without catch up is considered a standard practice19,20,21). Approximately 13% of children born SGA without catch up remain short and constitute a significant proportion of adults with short stature22). Many studies have shown that adult height is increased by GH therapy in these children19,21). Short-term GH treatment also reduces body fat while promoting lean body mass, which might reduce cardio-metabolic risk in SGA children23). Furthermore, a study in Sweden reported GH therapy was associated with a significant and cost-effective improvement in health and quality of life24). Although data concerning the safety of GH therapy in SGA are limited, the safety profile for idiopathic short stature indicated relatively low rates of adverse events25). Thus, U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency approved GH treatment for short stature in children born SGA. The other examples are premature adrenarche and polycystic ovarian syndrome in girls born SGA. Some hypothesized that adipose tissue expandability from insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in SGA girls leads to premature pubarche, followed by polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) in adolescents26).

A controlled trial reported the results of using metformin in girls born SGA with premature pubarche7). Girls receiving early metformin showed low visceral fat, reduced androgen, taller height, and low PCOS prevalence. The authors concluded that early metformin prevented or delayed the manifestations of hyperandrogenism and that the timing of treatment might be important. Therefore, it is important to define SGA not only to reduce perinatal morbidity but also to manage short stature, premature adrenarche and polycystic ovarian syndrome in children and adolescents.

2. Comparison of the new Korean birth weight curves with other curves including the Lubchenco curves

It is well known that there is racial and ethnic difference in birth weight27,28,29). Further, significant interactions were found between race and maternal variables, such as education, marital status, birthplace, and the month when antenatal care began. Thus, ethnicity and sex specific reference for birth weight must be made. Compared to the 2010 US intrauterine growth data10), new Korean references for birth weight values are slightly higher than those of the US for infants with GA less than 36 weeks. That's because our reference of 36 weeks represent 36 weeks plus 0 to 6 days, while the US expected GA was defined as the closest week (GA 36 weeks; 35 weeks +4 day to 36 weeks +3 day) by obstetrical history, prenatal ultrasound, and postnatal physical examinations. Thus, we made LMS curves adjusted by GA. The New Korean reference curves were almost the same as the 2010 US intrauterine growth curves, except that the 50th percentile value of GA over 38 weeks and 90th percentile value of GA over 35 weeks were lower than US references. These might be racial difference between White and Korean populations. White infants are known to be heavier, taller, and have a larger heads than Asians27,29).

When compared with New Japanese neonatal anthropometric charts for GA15), the new Korean reference values were slight lower in preterm but slightly higher in term. It is well known that different inclusion criteria and the heterogeneity of methods used to trace neonatal growth charts result in wide differences in the cutoff values. The main reason for these differences is that the new Japanese charts were made based on the data of subjects born only by vaginal delivery and divided by primiparity/multiparity. About 40% of the subjects in the new Korean references might be born by cesarean section30). Neonates born by cesarean section had lower birth weight in preterm31). Thus, the distribution of 10th percentile curves was skewed toward lower birth weights during the preterm period births delivered by cesarean section. The term baby's higher weight in Korean population might be an ethnic difference. The height and weight of Korean mother might be taller and heavier. The birth weight and length was also known to be related with mother's weight and height32). In previous Korean birth weight data divided by primiparity/multiparity also showed higher weight in term than that of Japanese population33).

When compared with the Lubchenco's data, the 90th percentile birth weight cutoff of Korean curves was lower than that of Lubchenco's and the 10th birth weight cutoff of Korean curves was higher after 32 weeks than the Lubchenco curves. Lubchenco curves were made from White neonates in 1948 to 196334). The differences of 90th percentile might be the racial difference between White and Asian. White infants are heavier and longer even in preterm. In 1950s, IUGR fetuses may have died in utero, delivered severely macerated, and not included in that database. Furthermore, recent advancement of high-risk pregnancies care resulted in extended periods of growth restriction in Korea. The differences of 10th percentile birth weight cutoff might be also explained in part by advanced high-risk pregnancies care and neonatal care nowadays10). Another component is the nutritional state of Korean mothers, which can be better than those of Colorado. Thus the Korean 10th percentile birth weight cutoffs are shifted up and as a result, the percentage of both LGA (especially GA under 36 weeks) and SGA can be underestimated by the Lubchenco curves compared with the new Korean birth weight curves. There are some limitations in the present study. First and, the most important limitation of this reference, like other population-based studies, is its cross-sectional nature based on birth certificates. Rather than longitudinal measurements of the same fetus over the course of gestation, the references are based on the birth weights of different infants born at different GAs9,35). Thus, preterm infants are somewhat smaller than fetuses of the same GA who remain in utero36). Second, we were unable to make references of length for GA, which is also important for determining SGA, because information about birth length was not included in the KOSIS data. The birth length for GA might be different between the 2010 US intrauterine growth data and the 2014 Japanese neonatal anthropometric data. Further research is needed in Korean as well. Third, we did not make separate charts for neonates from primiparous and multiparous mothers. It is well known that birth weights of infants of multiparous mothers are heavier than those of primiparous mothers by 20-50 g33). However, most of the subjects in this study were 1st baby as birth rate per woman is 1.14 in Korean. Finally, the new Korean references of birth weight were based on round off GA and the curves were made on nearest GA.

In conclusion, we calculated the means and percentiles of birth weight in Korean neonates by GA on the basis of KOSIS data. We created new sex specific reference curves for birth weight by GA using the data of almost all contemporary Korean neonates. We also created new cutoffs of SGA and LGA. As some SGA and LGA infants had short-term and long-term health risks, these data and curves provide useful information not only for endocrinologists but also for other specialists, including neonatologists in Korea for planning research or targeting to prevent metabolic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and CVD.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.