Estrogen receptor α polymorphism in boys with constitutional delay of growth and puberty

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

There were a lot of reports regarding associations of polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor α (ESR1). with many disorders. But, those with constitutional delay of growth and puberty (CDGP) are not known. Our aim is to find out any association between CDGP and ESR1.

Methods

In a total of 27 subjects, we compared 7 CDGP patients with 20 healthy controls with their heights and sexual maturity rates were within normal range. We selected three single nucleotide polymorphisms from intron 1 of ESR1 (rs3778609, rs12665044, and rs827421) as candidates, respectively.

Results

In genotype analyses, the frequency of G/G genotype at rs827421 in intron 1 of ESR1 was increased in CDGP boys (P=0.03).

Conclusion

The genetic variation of ESR1 can be a contributing factor of tempo of growth and puberty.

Introduction

Growth and puberty are influenced by genetic and environmental factors. The heritability of growth and puberty is reported about 75-90 and 50-80%, respectively. Even though the large proportion of them is affected by genetic factors, but it is difficult to elucidate a major one because of complex polygenic traits1-6).

The boys with constitutional delay of growth and puberty (CDGP) usually have short stature due to slow tempos of growth and are referred to pediatric endocrinologist. But, it may be a challenge to differentiate CDGP from pathologic short stature before onset of puberty, and genetic factors involved in CDGP are not clarified yet7-9).

There were several reports about associations of estrogen receptor α (ESR1) polymorphisms with bone mineral density, breast cancer, height, and age of menarche10-18). Also, the abundant amount of ESR1 is present in epiphyseal plates of long bones19). Therefore, we hypothesized that ESR1 can be a factor that controls the tempo of growth and puberty.

The purpose of this study is to determine whether polymorphisms in ESR1 are associated with CDGP in boys.

Materials and methods

1. Subjects

From July 2008 through August 2012, we recruited 27 boys who visited Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong for growth evaluation. Seven patients diagnosed with CDGP, which is defined as a condition in which the height of individual is at or below the 3rd percentile in the same sex and age group according to the Korean population-based reference20), annual growth velocity is greater than 4 cm, with delayed puberty and bone age, but, without evidence of systemic, endocrine, nutritional or chromosomal abnormalities7). To differentiate CDGP from hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or hypopituitarism, they underwent combined pituitary function tests8,9). Twenty boys with normal height and pubertal range were grouped as a control.

Height (cm) was measured using standardized equipment (Harpenden stadiometer Ltd., Crymych, UK). The height standard deviation score was calculated by (measured height - mean height)/standard deviation. The bone age was assessed by radiographs of the hand and wrist, using a method of Greulich and Pyle21). Midparental target height was calculated by (Father's height [cm] + Mother's height [cm] + 13)/2 in male.

All subjects and parents provided informed consent before the study commencement. This study was approved by the clinical research ethics committee at Kyung Hee University Institutional Review Board (KHNMC- IRB 2008-019).

2. Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples of subjects using DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The genomic DNA was amplified with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with forward and reverse primer pairs and standard PCR reagents in 10 microliter reaction volume, containing 10 ng of genomic DNA, 0.5 pM of each oligonucleotide primer, 1 microliter of 10X PCR buffer, 250 µM dNTP (2.5 mM each) and 0.25 unit Taq DNA Polymerase (5 unit/µL) (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea). The PCR reactions were carried out as follows: 5 minutes at 95℃ for 1 cycle, and 35 cycles at 95℃ for 30 seconds, 55℃ for 30 seconds, 72℃ for 30 seconds, followed by 1 cycle of 72℃ for 10 minutes. After amplification, the PCR products were treated with 1 unit each of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) (USB Co., Cleveland, OH, USA) and exonuclease I (USB Co.) at 37℃ for 75 minutes and 72℃ for 15 minutes to purify the amplified products. One microliter of the purified amplification products were added to a ready reaction mixture containing 0.15 pmol of genotyping primer for primer extension reaction. The primer extension reaction was carried out for 25 cycles of 96℃ for 10 seconds, 50℃ for 5 seconds, and 60℃ for 30 seconds. The reaction products were treated with 1 unit of SAP at 37℃ for 1 hour and 72℃ for 15 minutes to remove the excess fluorescent dye terminators. One microliter of the final reaction samples containing the extension products were added to 9 microliter of Hi-Di formamide (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA). The mixture was incubated at 95℃ for 5 minutes, followed by 5 minutes on ice and then analyzed by electrophoresis in ABI Prism 3730xl DNA analyzer. Analysis was carried out using Genemapper ver. 4.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Table 1 shows the primer sets and Tm used for the reactions.

3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 8.02 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The demographic characteristics of the control and patient group were compared with Kruskall-Wallis test. Each result was presented as the mean±standard deviation. The value of P<0.05 is considered as statistically significant. The frequencies of allele and genotype, and the departures of the genotype distribution from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for each single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Linkage disequilibrium was calculated with the Haploview ver. 3.2 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). The genotype-specific risks were estimated as the odds ratios with associated 95% confidence intervals using conditional logistic regression analysis.

Results

1. Subjects

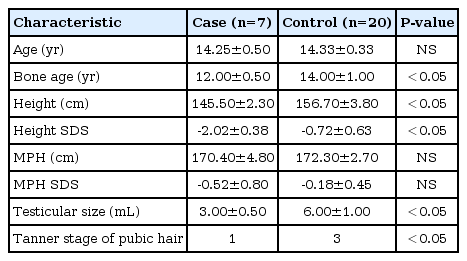

The chronologic age of boys with CDGP is 14.3±0.5 years and controls is 14.3±0.3 years. The bone age (12.0±0.5 years) was less than chronological age in CDGP patients with significant statistical difference (P<0.05). However, there were no significant differences between bone age (14.0±1.0 years) and chronological age in the control group. Mean height standard deviation score (SDS) in CDGP group was less than that of the control group (P<0.05), but there were no differences in midparental target height SDSs between CDGP and control group. For sexual maturity rates, data showed Tanner stage 1 in CDGP patients and 3 in control group (Table 2). The pituitary function tests were performed in all CDGP patients, and the results were within normal limits (The data was not shown).

2. Distribution of ESR1 polymorphisms

Three SNPs were analyzed; rs3778609, rs12665044 and rs827421 in intron 1 of ESR1. The rs3778609 genotypes were C/C, 42.86%; C/T, 28.57%; and T/T, 28.57% in CDGP patients, and 50.0%, 45.0% and 5.0% in controls. The rs12665044 genotypes were C/C, 42.86%; C/T, 28.57%; and T/T, 28.57% in CDGP patients, and 45.0%, 45.0%, and 10.0% in controls. The rs827421 genotypes were A/A, 14.29%; G/A, 42.86%; and; G/G, 42.86% in CDGP patients, and 35.0%, 60.0%, and 5.0% in controls. Therefore, the frequency of G/G genotype at the rs827421 in intron 1 of ESR1 was increased in CDGP patients with odds ratio of 19.15 (P-value permutation=0.03) (Table 3). In haplotype frequencies, there were no significant differences between cases and controls (Table 4).

Discussion

CDGP is a condition with short stature due to slow tempo of growth and puberty without any evidence of systemic, endocrine, nutritional, or chromosomal abnormalities. Although the heights of children with CDGP are lower than 3rd percentile before onset of puberty, their adult heights can be in the range of target height. Therefore, in those children, many interventions and modalities of promoting growth are usually unnecessary1,3).

To differentiate CDGP from other pathologic short stature, for example, subcategory of idiopathic short stature or hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, many studies focused on the genes and hormonal evaluations related with pubertal timing were done2,4-7). But, it is a challenge because of similar phenotypes, overlapping of hormonal levels, and still unidentified genetic factors of them7).

In aspect of phenotype, the complete discrimination between CDGP and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism may be possible after puberty8). In hormonal studies, basal serum levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone or inhibin B, stimulation tests with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or agonist and human chorionic gonadotropin were reported to be useful7-9).

The genetic studies about pubertal timing or CDGP are more complicated1,4). Although the inheritance is likely complex, several studies to find out major genes related with them were committed because some predisposing genetic factors have a dominant effect22). Genome wide association studies are useful method to identify the linkage of polygenic inheritance, and the Early Growth Genetics Consortium in Europe found associations of LIN28B, MAPK3, and ADCY3-POMC with pubertal height growth, menarche, body mass index, and early puberty2). Also, many candidate genes were studied for a long time.

Banerjee et al.23) studied if there is any association of leptin or leptin receptor polymorphism with CDGP, but no association was found, leptin was thought as only a prerequisite factor for puberty. GnRH and GnRH receptor (GnRHR) genes were also strong candidates because puberty begins with GnRH pulse, and Lin et al.24) found a homozygous R262Q mutation in GnRHR in two boys with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism from one family. However, Sedlmeyer et al.25) studied and concluded genetic variation in GnRH1 and GnRHR was not likely to be a modulator of pubertal timing in general population.

Pugliese-Pires et al.26) reported the cases of CDGP with novel inactivation mutations in the GHSR gene, and he thought abnormalities in ghrelin receptor function may influence the phenotype of CDGP. Kauffman et al.27), and Seminara et al.28) studied Kiss1 and GPR54 as candidate genes in mice. Tommiska et al.29) and Ong et al.30) also thought and studied LIN28B as a related gene with obesity and earlier puberty. But, Gajdos et al.31) and Vaaralahti et al.32)'s studies told us that the gene variants or defects found in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism are not related with CDGP. Finally, it is still a conundrum to deciphering the genetics of pubertal onset, timing, and CDGP. In 2010, Borjesson et al.33) suggested the low concentration of estrogen may be involved in pubertal growth spurt and the interaction of high concentration of it and its receptor (ESR1) can be a factor of epiphyseal plate closure in long bones.

ESR1 is in chromosome 6 and composed of 8 exons in human12). Futhermore, there were several studies regarding the associations of ESR1 polymorphisms, especially in intron 1 region due to possibly promoter effects, with height variation and onset of menarche14-18). Therefore, our hypothesis is that ESR1 can be a factor that controls the tempo of growth and puberty and a marker of CDGP.

In this study, at the rs827421 SNP locus in intron 1 of ESR1, we found the frequency of G/G genotype was increased in CDGP patients. We thought that this means it may be a contributing factor of pubertal growth and a marker of CDGP. This is the first study about the association of ESR1 with CDGP, but, there is a limitation that due to the relatively small number of cases and a difference of numbers between the case and control group. Further studies are required in a large population cohort.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.